More than at any other time of the year, Easter foregrounds the image of Jesus Christ. Reenactments of the Stations of the Cross, religious imagery in magazines and newspapers, and biblical specials aired on television all show us the events of Easter, but none can answer the question: what did Jesus really look like?

Though such a concern seems trivial, our ideas about Jesus’ looks and appearance are worth considering because any representation of Jesus reveals the values of the times and places in which it was produced. When I think of Jesus, I must admit that to me, he’s conventionally attractive. He has longish brown curly hair; he’s tall, lily-skinned and dewy-eyed. For a carpenter, he’s curiously light on muscle. Being young and good-looking, this Jesus bears a striking resemblance to the late singer Jeff Buckley, which means I’d just as soon date him as be saved by him.

Probably others, whether Christians or not, would paint a similar portrait of Jesus. It’s the dominant image of Christ we can’t shake in the contemporary West—a legacy of two millennia of Western religious art and the last hundred years of (mostly Western) cinematic depictions of the man from Nazareth.

Probably others, whether Christians or not, would paint a similar portrait of Jesus. It’s the dominant image of Christ we can’t shake in the contemporary West—a legacy of two millennia of Western religious art and the last hundred years of (mostly Western) cinematic depictions of the man from Nazareth.

The saturation of such images in our culture means that it is practically impossible to not visualise Christ in the terms described above—curious given that no one alive today actually knows what Jesus looked like. None of the gospel accounts of Jesus’ life, from where our information about him primarily derives, contain any reference to how tall he was, whether he was stocky or lean, whether his eyes were piercing or whether he had a squint.

And yet Christ is almost never portrayed in less than appealing terms due to the age-old assumption that looks equal worth. In this context, Jesus’ beauty is more symbolic than physical, or his outward beauty is a sign of his inward goodness. Still, it’s debatable whether this ‘beauty as metaphor’ is uppermost in the minds of many. More than likely, we’ve junked the symbolism and just assumed that Christ was something of a hottie.

American artist Warner Sallman (1892-1968) painted the most definitive images of Christ of the last century. His Head of Christ (1940) bears the hallmarks of the iconic Jesus—long brown hair, beard, Anglo features, slim, conventionally attractive. Art scholar Erika Doss notes that the popularity of Head of Christ was at least partly due to its resemblance—in terms of style, colouring and pose—to publicity shots of movie stars of that era. Which indicates that there’s little chance Sallman’s Jesus would ever have been pictured as less than handsome since he was portrayed in similar terms to the matinee idols of that day.

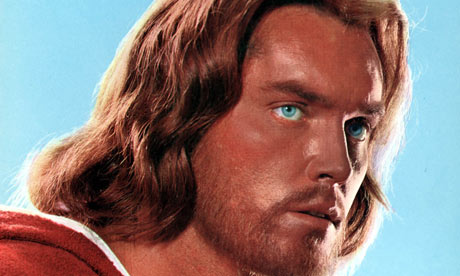

Not only has it been assumed that Christ was good-looking, but also very, very White. Both conceits were taken to the extreme in Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961). Critics dubbed the film ‘I was a teenage Jesus’ in reference to the hunkiness of its Jesus, played by Jeffrey Hunter. (For a more recent equivalent to Hunter, think Brad Pitt in Legends of the Fall). Given the assumed gorgeousness of Jesus, Hunter’s handsomeness isn’t that remarkable. What is noteworthy is how Caucasian this Christ is, given that he was born in first century Palestine and was, presumably, of ‘Middle-Eastern appearance’.

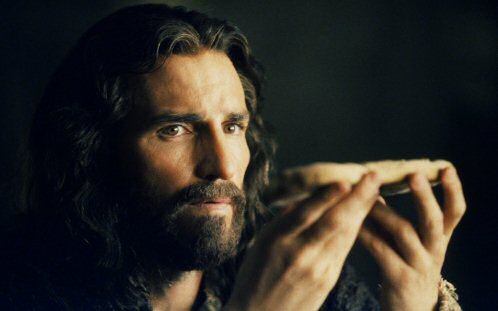

However, judging from more recent movies, the political incorrectness of a European Jesus is slowly being recognised. Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) starred Jim Caviezel as a browner but still essentially Anglo Jesus. Perhaps in concession to the implicit racism of portraying yet another White saviour, Caviezel’s blue eyes were digitally coloured brown for the film and he wore a prosthetic nose.

Yet this cosmetic window-dressing, and even the spectacle of Caviezel’s beaten, tortured and ultimately crucified body can’t quite conceal the fact that his Christ is really, really good-looking. Caviezel stands at least a foot taller than your average Jew of that time, and his broad shoulders, lean, bronzed frame and chiselled features (fake nose or not) make his Christ cut an impressive, if bloody, figure. Clearly, if Jesus is going to die for us, we want him to look good doing so.

But all representations of Jesus must confront, sooner or later, the Jesus of the gospels—a figure who is countercultural in the extreme. As recounted in the Bible, Jesus’ actions, his manner and his message of salvation challenged, maddened, and outraged the social, political and religious institutions of his time—so much so that he died for the offence he caused. So doesn’t it stand to reason that Jesus would also frustrate us on this point of his supposed pleasing appearance?

But all representations of Jesus must confront, sooner or later, the Jesus of the gospels—a figure who is countercultural in the extreme. As recounted in the Bible, Jesus’ actions, his manner and his message of salvation challenged, maddened, and outraged the social, political and religious institutions of his time—so much so that he died for the offence he caused. So doesn’t it stand to reason that Jesus would also frustrate us on this point of his supposed pleasing appearance?

Stephen D. Moore, Professor of New Testament at Drew University in New Jersey, argues in his book God’s Beauty Parlour: And Other Queer Spaces In And Around The Bible that the remaking of Christ into our idealised image of beauty “ensure[s] minimal disturbance to the status quo” (2001: 128). Moore implies that the more beautiful we make our Jesus, the less offensive he becomes to us. This status quo, Moore notes, values looking good over being good, and promotes physical transformation over social transformation. His comments feel particularly apt for a Western culture that prides itself on the art of the extreme makeover of all areas of life—job, figure, love life, cooking, house, garden, and lifestyle.

For an attractive Christ, or a Jesus who is a better-looking version of us, effectively endorses the way of life so desperately sought after in the contemporary West, where looking good is an indispensable part of the ‘good life’. Submitting Jesus to the values of our culture—that patently worships the new, the attractive, the young, the White, over the wizened, the ugly, the infirm, the non-White—is much safer than heeding his often blistering critique of power and our failure to love God and each other as we should.

The absence of detail in the gospels about Jesus’ appearance says much about the concerns of the authors. But for an image-conscious culture such as ours where beauty is often a measure of worth, such absence grates inasmuch as we can’t confirm whether or not God sanctions our quest for physical loveliness.

In fact, the only thing the bible has to say about the appearance of Jesus suggests that even though he was divine he certainly didn’t look it. A line widely regarded by biblical scholars as a prophecy about God’s chosen saviour declares “He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him” (Isaiah 53:2). Meaning that at best, Jesus may not have been much to look at. At worst, he might have been less Jeff Buckley and more, well, plain ugly.

Beauty often makes us tremble at its sight. But in the context of our makeover culture, a physically attractive Christ that fulfils rather than challenges the beauty ideals of Western culture seems rather suspect. If, as Moore suggests, a good-looking Christ focuses our attention on outward rather than inward transformation, and personal rather than collective change then perhaps our tendency to airbrush Christ into perfection is an effective way to keep the real man (the real God?) at bay. Jesus must be rolling in his grave—unless, of course, he rose up from it.

Dr Justine Toh is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and lectures in Cultural Studies at Macquarie University.

This article originally appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald