My kids brought their report cards home last month. I’d been thinking about the election campaign, and about society’s obsession with productivity. I’d been wondering how ‘the unemployed’ and ‘pensioners’ might feel — like a burden? Like a problem to be solved?

I’d been thinking about my own productivity too as an employee, as a freelancer, as a parent; about what left me feeling satisfied, worthy, competent, or guilty, unproductive, unfulfilled.

I’m convinced we should value people for who they are, not what they do, or don’t or cannot do. And yet I catch myself, thinking about, talking about, how much I have or haven’t done on any given day; forgetting to reflect on how I have behaved, on the kind of parent, wife, colleague, friend, daughter, neighbour, stranger, that I’ve been.

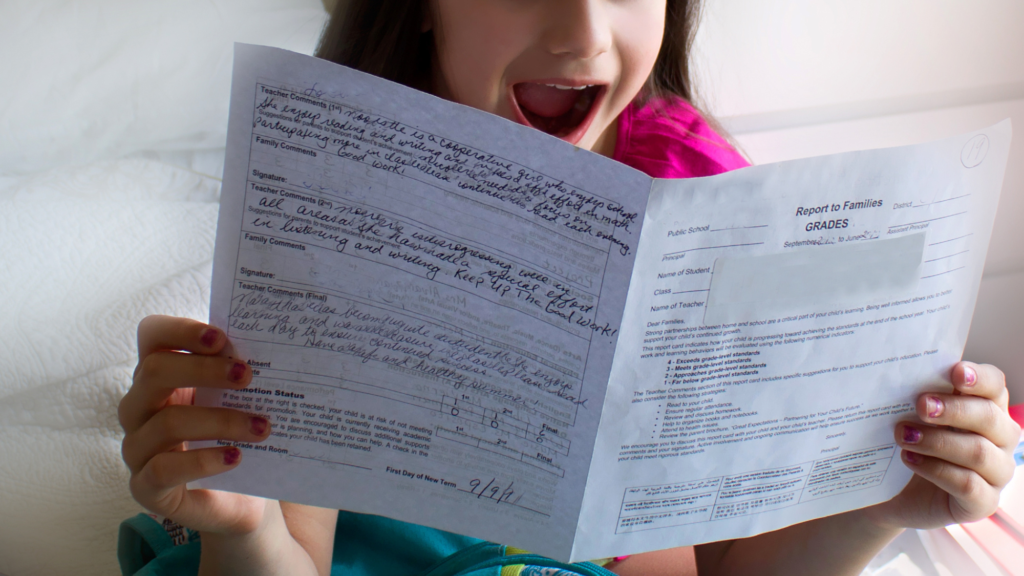

Such thoughts were on my mind when those reports landed on our kitchen bench. Ten ‘learner dispositions’, three possible ratings. I wanted our children to ‘actively participate in learning’ and ‘aspire to do their best’, but more than that, I hoped that they were kind. I wanted them to be good students, but more than that, good friends.

I skipped past ‘uses time effectively’ and ‘works well independently’, to ‘softer’ (and yet harder) skills: ‘responds respectfully’, ‘listens to others’, ‘works well in groups’. Were they working towards expectations? Meeting expectations? Exceeding expectations? But also: was I?

If I cared more about the kind of people they were than how they were performing, what about myself? How would I evaluate my performance? And how would they evaluate me? I wondered, and then I dared to ask.

My 10- and 8-year-olds were all too happy, ALL TOO HAPPY, to oblige. They didn’t hesitate when it came to working well independently and using time effectively: ‘exceeds expectations’. Apparently I’m also very good at working in groups (‘cos of all the time you spend with your friends!).

But in other areas, including listening to others, I was just ‘meeting expectations’. And when it came to responding respectfully, I was merely ‘moving towards’ them.

When pressed, they pointed out that I wasn’t always calm and respectful when things went wrong. I thought about my tone when we were running late; when I randomly declared a harmless mess intolerable; when my frustration about something they did nothing to provoke landed on them — they had a point.

I could be listening better too. I often felt frustrated when they seemed to ignore me, but how often did I tune their voices out?

Why is it so easy, I thought, to be a hypocrite? To say one thing, to think it, too, then blindly do another? To forget what really matters and fixate on what does not?

I want to care more about my character than my productivity or performance, more about others than myself.

Why do politicians so rarely say they’re sorry, they messed up, before they are found out and they are forced? Perhaps they, too, forget to think not only about what they have achieved, but how they have behaved; about the kind of person they have been and want to be.

I want to care more about my character than my productivity or performance, more about others than myself. I’m destined to fail. But I can keep ‘working towards expectations’. And at the end of every day, I can ask myself how well I have loved instead of how much I have done.

I can also practise saying sorry, and dare to hope my failures really are forgivable; not because I am deserving but because I know, full well, that I am not.

Emma Wilkins is a Tasmanian journalist and freelance writer, and an Associate of the Centre for Public Christianity.

This article first appeared in Eureka Street.