At a time of wars on terror, devastating earthquakes, financial meltdowns and the threat of environmental catastrophe, post apocalyptic films and novels have captured the popular imagination. Most of us can, without too much effort, envisage a totally broken society—nightmares of utter devastation where all structures, constraints, and systems that make life tolerable have collapsed. Yet few could create a sense of what that world might look like in a more haunting and disturbing manner than Cormac McCarthy.

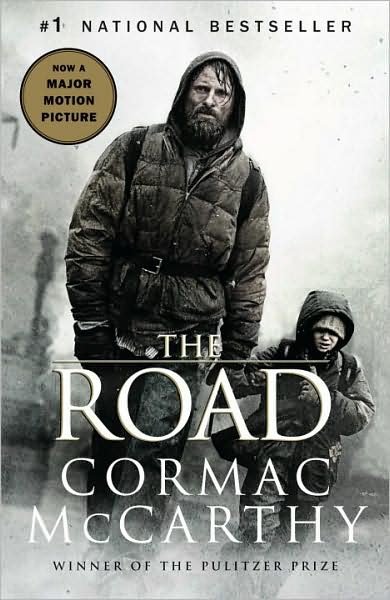

Most well known for No Country for Old Men, McCarthy is regarded as one of America’s great novelists at the height of his powers. In The Road he delivers a masterful reading experience of terrifying beauty.

Most well known for No Country for Old Men, McCarthy is regarded as one of America’s great novelists at the height of his powers. In The Road he delivers a masterful reading experience of terrifying beauty.

The premise of the story is straightforward. A man and his young son walk ‘the road’ heading south towards the coast through an America brought to waste by a catastrophic event ten years earlier. Is it nuclear war? Global warming? A meteor? We never find out. Whatever the cause, the effect is total. The world is changed. Civilisation has ended. Thick ash blankets the earth. A constant dark cloud produces nights of inky blackness, and shortened days of only feeble and ineffective sunshine.

The scenes constructed by McCarthy are truly horrifying. Debris litters the road, as do cars containing gnarled corpses ‘shrunk to the size of a child … ten thousand dreams encapsulated within their crozzled hearts’—images that form a jolting reminder of a past that is lost forever. It is into this world that the reader takes a journey with the man and his son who remain nameless throughout.

Signs of life are scarce. Towns are empty and houses and buildings are abandoned to looters and vandals. The few remaining people exist in a world of brutality and desperate survival. Think New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina on a global scale, as the thin veneer of civilisation is removed to reveal the fragility of our constructed lives.

| ‘By then all stores of food had given out and murder was everywhere upon the land. The world soon to be populated by men who would eat your children in front of your eyes and the cities themselves held by cores of blackened looters who tunneled among the ruins and crawled from the rubble white of tooth and eye carrying charred and anonymous tins of food in nylon nets like shoppers in the commissaries of hell.’ (192) |

Reminiscent of C.S. Lewis’s metaphoric images of hell in The Great Divorce, McCarthy skilfully evokes an apocalyptic landscape stripped of all colour, beauty and grace.

| ‘He walked out into the gray light and stood and he saw for a brief moment the absolute truth of the world. The cold relentless circling of the intestate earth. Darkness implacable. The blind dogs of the sun in their running. The crushing black vacuum of the universe. (138) |

There are brief allusions to a past life; past loves, moments of beauty, colour and the wonder of the intact natural world. Recalling a time at a beach stroking the hair of his lover as she slept, the man had thought ‘if he were God he would have made the world just so and no different’ (234). He rarely thinks of those days now. Those memories have become a cruel joke to someone living out a real life horror story. ‘There were few nights lying in the dark that he did not envy the dead.’ (245)

McCarthy writes stories that are rich in theological reflection and The Road is no different in this regard. Given the subject matter it may come as a surprise that McCarthy has stated that while his earlier novel Blood Meridian was mostly about human evil, The Road is mostly about human goodness.

The goodness is found in the sense that human beings carry within them something of immense value and worth that is not easily erased, and this aspect of the story—encapsulated with such pathos in the relationship between the man and the boy—is its most enduring and powerful element. It’s a heartbreaking love story and an inspiring reminder of the things that matter most.

The man’s monumental efforts to survive are entirely about the boy in his care. Where his wife, seeing the reality of what lay ahead of them, had given up years before, the man refuses to let go. He is kind, forgiving, and fiercely protective. There is great beauty and tenderness in the way he cares for the boy, constantly reassuring him, telling him everything’s going to be OK, when they both know it will not. It is in this relationship where we are given a bright note of hope. ‘We’re still here’ he tells the boy, ‘a lot of bad things have happened but we’re still here.’ (287)

The man’s monumental efforts to survive are entirely about the boy in his care. Where his wife, seeing the reality of what lay ahead of them, had given up years before, the man refuses to let go. He is kind, forgiving, and fiercely protective. There is great beauty and tenderness in the way he cares for the boy, constantly reassuring him, telling him everything’s going to be OK, when they both know it will not. It is in this relationship where we are given a bright note of hope. ‘We’re still here’ he tells the boy, ‘a lot of bad things have happened but we’re still here.’ (287)

The boy himself represents the best aspects of human nature—a remnant of virtue on a moral wasteland. He’s the one person left who wants to care for strangers— a shuffling, almost blind old man with whom the boy wants to share their meagre rations, a little boy he thinks he sees in a city who he wants to go back and rescue. He begs his father to show mercy to a thief who almost gets away with their only possessions. It’s more than innocence he displays. It’s goodness.

‘We’re the good guys,’ the man constantly tells his son. ‘We carry the fire.’ What is this fire? The wonder of being human? The divine spark? The image of God? Something else?

Where is God in all this? There are places in the story where it would appear that God, if he ever existed, has long ago left this scene; that the appearance of transcendence is merely a human construction. An old straggler on the road declares:

| ‘I’m past all that now. Have been for years. Where men can’t live gods fare not better. You’ll see. It’s better to be alone.’ (183) |

There are definitely strong currents of existential meaninglessness in this story and some will feel that to be its lasting impression. McCarthy describes the ravaged world of The Road as ‘a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again.’

Yet despite all the waste and destruction there remains a defiant and enduring hopefulness that is at the core of this work. Moments of grace, the possibility of love, the possibility of God. Frequently the boy and the man feel like they are being watched. Is it a benevolent presence or something sinister? Are they being hunted or watched over? Their unlikely survival and fortunate escapes imply the latter. When they stumble upon an intact underground storeroom packed with food and provisions, it feels like a miracle. They eat. They sleep in sheets on a bed. The man washes his son’s putrid hair. It’s a brief but exquisite respite on the gruelling journey to nowhere.

At the end a woman embraces the boy—a mother for him at last. She speaks to him about God and tells him that ‘the breath of God was his breath yet though it pass from man to man through all of time.’ There’s no triumph here, but nor is there irrevocable despair.

The Road is no fairytale and yet it shares at least one important element of the fairytale genre—not the elimination of sorrow and failure, but the denial of universal final defeat. It’s what Tolkien described as, ‘a glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.’

The Road also calls with great poignancy beyond the walls of the world to something or someone of transcendence; to something beyond our circumstances and through which we might also resist universal final defeat. McCarthy is uncertain of what that thing might be, remaining content to reflect on the undeniable mystery of it all.

But the notes of optimism and the somewhat bright ending seem to give space to the possibility of divine redemption of some kind. The breath of God may in fact continue through the remnant. Against a backdrop of such horrifying bleakness that flicker of light represents a surprising image of hope.

Simon Smart is the Head of Research and Communications at CPX