As citizens of a scientific age we assume that any document that mentions the origins of the world must be concerned with the mechanics of those origins, that is, with how the universe was made. But that is surely anachronistic. One of the first rules of historical enquiry is: ‘thou shalt not read contemporary assumptions into ancient texts!’ In the case of Genesis we absolutely must remember that this text was composed two and half thousand years before the scientific era, at a time when intellectuals were not even asking questions about the mechanics of creation.

Paganism and biblical ‘subversion’

So what is the purpose of this portion of Scripture – the first chapter of Genesis – according to biblical historians? In a nutshell, the opening section of the Bible appears to have been written to provide a picture of physical and social reality that debunks the views held by pagan cultures of the time. In short, Genesis 1 is a piece of subversive theology.

To anyone familiar with the Old Testament this subversive, anti-pagan intent will come as no surprise. One of the golden threads of the Old Testament is its sustained critique of the pagan religions of Israel’s neighbours – the Egyptians, Canaanites and Babylonians. The first two of the Ten Commandments, for instance, are all about shunning the pagan deities of the ancient world.1 Moreover, the book of Psalms – the hymnbook of ancient Jews – regularly and explicitly declares that the creation owes its existence not to the pagan gods but to Yahweh, the God of Israel.2 In Jeremiah 50:2 the Babylonian creator god, Marduk, is explicitly named and denounced.

Given the prominence of this motif in the Old Testament it would be surprising if the Old Testament’s longest statement about creation did not take a swipe at pagan understandings of the universe. We do not have to speculate about this. Through a stroke of very good fortune, scholars are now able to see just how the writer of Genesis went about his task of debunking his ancient rivals.

Enuma elish: a Babylonian Creation Myth

Just as Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was about to be published (1858), archaeologists working in Mosul in Northwest Iraq (ancient Mesopotamia) in the early 1850s discovered tablets almost three thousand years old.3 On these tablets was written in cuneiform an account of creation held sacred by Israel’s near and dominant neighbours, the ancient Babylonians. Suddenly, we were in a position to compare Genesis 1 with a pagan creation tradition, which according to most scholars predates the biblical account by several centuries.4

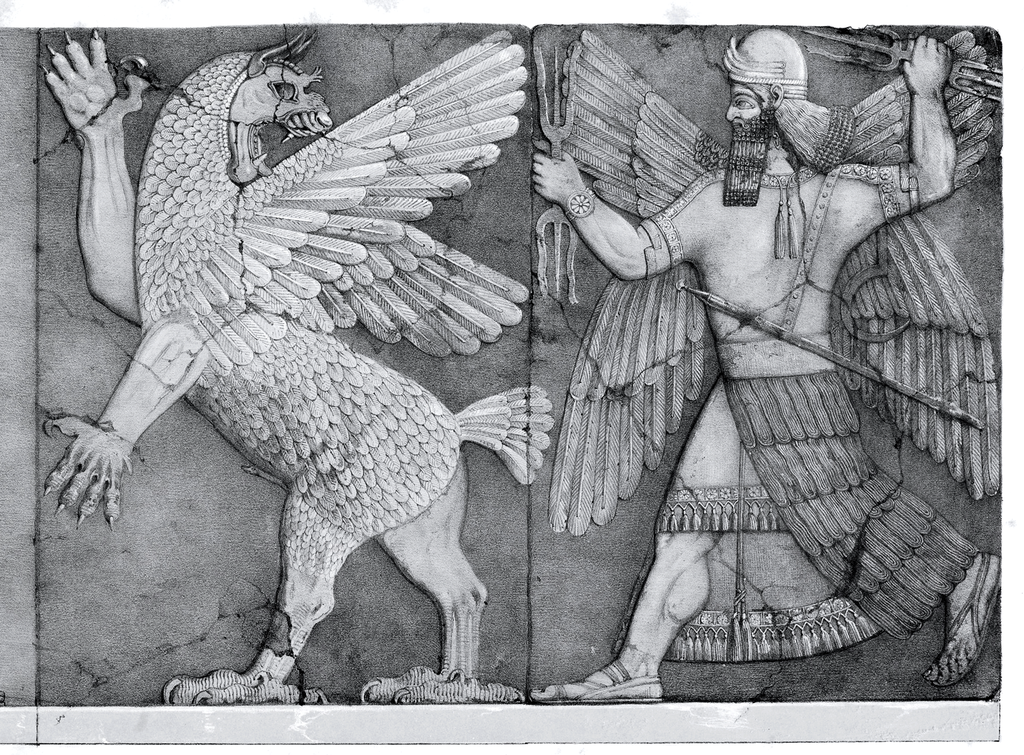

We now know that if you were raised in Babylonian culture of the second millennium BC your view of origins would have been based on a story that was as popular as our Santa Claus fable and as socially influential as Darwinism itself. The story came to be called Enuma elish, the opening words of the epic.5 To sum up a long, seven-tablet story short, Enuma elish essentially narrates the violent adventures of the original family of the gods. Apsu and Tiamat, the father and mother of the gods, go to war against their offspring because of all the chaos the youngsters bring to their peaceful kingdom. Both divine parents are killed by the greatest of the junior warrior gods, Marduk, who goes on to fashion the universe out of the various bits and pieces of the vanquished gods.

As bizarre as all this sounds, stories like Enuma elish were critical expressions of ancient people’s understanding of the purpose and significance of life. Indeed, Enuma elish was so important in Babylon it was publicly recited in the capital every New Year’s day. It was their national mythic story. It was Christmas and ANZAC Day rolled into one.

The fascinating thing about all this is that Genesis 1 shares numerous thematic and stylistic features with the pagan myths scholars have uncovered in the last 150 years. Enuma elish provides the simplest point of comparison:

- Both Enuma elish and Genesis begin in the first paragraph with a watery chaos at the dawn of time. Instantly, then, we know we are in similar thought-worlds;

- Both stories proceed in seven movements: seven days in Genesis 1 and seven scenes written on seven tablets in Enuma elish;

- The narratives even share the same order of creation, beginning with the heavens, then the sea, then the earth, and so on;

- Both accounts climax with the creation of men and women, which occurs in the sixth scene or day in both accounts.

After initial speculation that Genesis had perhaps plagiarized pagan creation motifs,6 it soon dawned on scholars that what we find in Genesis 1 is philosophically antithetical to the message of these other myths. Historians soon realized something that they should already have expected given the criticism of pagan creation motifs found elsewhere in the Old Testament: Genesis 1 is a polemic against pagan cosmology and theology. Genesis uses stylistic elements of its pagan equivalents in order very cleverly to debunk the view of the world expressed in those traditions. The parallels constitute not emulation or endorsement of paganism but a parody or subversion of it. Genesis storms onto the ancient Middle Eastern stage with guns blazing, so to speak, making profoundly controversial claims about God, the environment and the purpose of human life.7

Exactly how Genesis achieves these subversive aims is the concern of the remainder of this article.

Genesis storms onto the ancient Middle Eastern stage with guns blazing, making profoundly controversial claims about God, the environment and the purpose of human life.

The Solitary God

The most prominent theme in Genesis 1 will have struck ancient pagan readers as a perverse novelty. The creation of the universe, says Genesis, was a solo performance. Behind the entire cosmos, in all its intricacy and variation, there is just one God. To give it a modern philosophical tag, Genesis 1 proclaims an uncompromising ‘monotheism’. It does this in a number of ways.

A striking introduction

Firstly, our text begins with a striking introduction: ‘In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.’ The writer does not bother to warm up his readers to the notion of one Creator; he puts it on the table up-front. A single God, says Genesis, created not just this particular mountain or that particular constellation but the ‘the heavens and the earth,’ which is the ancient way of saying ‘everything’.

A solo performance

Secondly, the chapter has just one performer. There is plenty of activity in the account – lots of speaking, making, seeing, separating, naming and so on – but only one actor. The second paragraph sets up the pattern well:

And God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light. God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light “day,” and the darkness he called “night.” And there was evening, and there was morning – the first day (Gen 1:3-5).

Compared with other creation accounts of the time, Genesis 1 is a conspicuously lonely affair.

The use of ‘god’ instead of ‘Yahweh’

The third way the passage proclaims monotheism is subtle but highly effective, especially for ancient readers. It has to do with the use, or rather non-use, of God’s personal name. Pagan creation myths always named their gods so that readers could know which god did what. In the Babylonian Enuma elish no fewer than nine separate deities are named in the first two paragraphs.8

The ancient Jews also had a personal name for their god: ‘Yahweh’, or the more anglicized, ‘Jehovah’,9 and it appears many times throughout the rest of Genesis. What is fascinating is that of the thirty-five references in this chapter to Israel’s Lord, not one employs the divine name. The author simply uses the noun ‘God’ – elohim in Hebrew.10 The effect of this is to undercut any suggestion that Yahweh was simply a Hebrew member of the pagan pantheon. ‘There is not Yahweh and Apsu and Tiamat and so on,’ says the author of Genesis. ‘There is just “God”.’ And by repeating the noun thirty five times the writer makes his point loud and clear.

Coherence in Creation

A corollary of pagan polytheism was a belief in the essential incoherence or randomness of the universe. In Enuma elish, for example, the physical world is said to have been fashioned as an after-thought, out of the bloody carnage of the war of the gods. The creation, in this view, is ‘haphazard’ in origin and ‘tainted’ in character. This was the broad viewpoint of ancient societies.

By contrast, Genesis 1 insists upon the elegance and intention of creation, in other words, upon its coherence. The universe is not a mindless collection of unpredictable forces, but the ordered accomplishment of a single creative genius. Monotheism in the Creator, says Genesis, results in coherence in the creation. The theme is emphasized by the 1st-century Jewish intellectual Philo in his On the Creation. It is found at almost every point in the biblical chapter.

The number ‘7’ and wholeness

In a previous article (The Genre of Genesis 1) I mentioned the artful use of multiples of seven throughout the chapter. In accordance with Hebrew literary conventions, this underlines the ordered perfection of creation. Philo devotes fifteen pages to the brilliance of the number seven. He begins: ‘I doubt whether anyone could adequately celebrate the properties of the number 7, for they are beyond all words’ (On Creation 90).11

The careful structure of the passage

A more obvious device is the careful literary structure of the passage. Each creative scene follows a deliberate four-fold pattern:

- A creative command (‘let there be light,’ for example) followed by,

- A report of the fulfillment of the command (‘and there was light’),

- An elaboration of creative detail (‘he separated the light from the darkness’) and, finally,

- A concluding day-formula (‘and there was evening, and there was morning – the first day’).

This pattern carries on through the whole account. The effect of all this is to underline the order and coherence of creation.12

Repetition of the word ‘good’

The repeated affirmation of the ‘goodness’ of the creation serves the same point. Verses 4, 7, 12, 16, 21 and 25 tell us that what God made ‘was good’. The seventh and climactic reference in verse 31 says that the creation ‘was very good.’ One gets the impression that the author is trying to counter the low view of creation present in just about every pagan culture of the time.

The demystification of the heavens

The final contribution to this theme of coherence is particularly subversive in an ancient context. Many ancient societies worshipped the sun and moon as gods in their own right.13 Genesis 1, however, describes these heavenly bodies simply as ‘lights’ – a big light for the day and a small one for the night:

And God said, “Let there be lights in the expanse of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark seasons and days and years, and let them be lights in the expanse of the sky to give light on the earth.” And it was so. God made two great lights – the greater light to govern the day and the lesser light to govern the night (Gen 1:14-16).

The author in fact refuses to use the normal Hebrew words for sun and moon, shamash and yarih, which may have been construed as divine names corresponding to Amon-Re in Egyptian tradition. These lights, moreover, are said to have been given by God to serve the inhabitants of the earth, rather than to be served by them. Anyone familiar with paganism will not have failed to see the significance of such comments.

The creation is not random or possessed by spiritual powers, says Genesis 1; it is the coherent masterpiece of one almighty being.

The number symbolism, the careful structure, the affirmation of the creation’s ‘goodness’, and the demystification of the heavenly bodies, all combine to challenge pagan notions of the capricious nature of the physical world. The creation is not random or possessed by spiritual powers, says Genesis 1; it is the coherent masterpiece of one almighty being.

The Place of Men and Women

The subversive intention of Genesis 1 reaches its climax in its description of the place given to men and women in the world by the Creator.

Man in Enuma elish

As I mentioned earlier, Enuma elish essentially recounts a primeval war of the gods. The eventual victor is a young deity named Marduk. He and his armies destroy the patriarch and matriarch of the gods and out of the bloody remains create the various items of the universe. The gods who had supported these vanquished foes were sentenced to an eternity of servitude, collecting and preparing food for the victors.

Here is where human beings come in. The defeated gods begin to complain about the sheer indignity of being used merely to fetch food for other gods. They petition Marduk to create some other creature more well-suited to a life of slavery. The idea pleases Marduk and so, out of the goodness of his heart and the pools of blood left over from the battle, he fashions a man, a being whose central task in life is to serve the gods with food offerings:

When Marduk heard the complaints of the gods, he said: ‘I will establish a savage, ‘man’ shall be his name. He shall be charged with the service of the gods, that they might be at ease!’ Out of Kinju’s blood they fashioned mankind. Marduk imposed the service on mankind and let free the gods (Enuma elish, Tablet 6).14

The clear ‘message’ of the story is that humans ought to know their place at the bottom of the divine scheme of things. Their role is to serve the needs and pleasures of the gods.15

It is against just such ancient views of humanity that our passage has something striking to say. According to Genesis 1, men and women lie at the centre of the Creator’s intentions and affections for the world. The theme is conveyed in a number of ways.

Interruption of the rhythm

First is the deliberate interruption to the rhythmic structure of the chapter. I explained earlier that each creative scene follows a careful four-fold pattern: a creative command followed by a report of the fulfillment of the command, an elaboration of creative detail, and a concluding day-formula. What I did not say is that in the final scene this pattern breaks down. Verse 26, which describes the creation of humankind, is introduced not with a creative command but with a divine deliberation, a pause in the rhythm of the text, which tells us that something special, is about to happen.

God does not say ‘Let there be man’ as we should expect from the pattern set up throughout the chapter. Rather, the Creator declares to himself: ‘Let us make man in our image.’ The break in the rhythm is obvious and flags to readers that they have arrived at something special, a climax in the message of the chapter. The contrast with Enuma elish is striking. Humans were last in the list of creative acts in Enuma elish because they were an afterthought. They are last in the list of creative acts in Genesis because they are the highpoint of the account. Philo highlighted the same point two thousand years ago (On the Creation 77-82).

Men and women in the ‘image of God’

The contrast with paganism deepens in the elaboration of the act of human creation. In Enuma elish the first man, as we saw, was fashioned out of the blood of the vanquished god, Kinju. The man, in other words, was a product of the loser’s left-overs, to put it crudely. In Genesis 1, however, we are told that men and women were created in the very image of God. Verse 27 makes the point emphatically:

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.

The phrase, ‘the image of a god’ was used in two related ways in antiquity.16 Firstly, it was used of the many statues of deities set up throughout pagan cities. These were regarded as representatives, ‘images’, of the divine presence. The second use of the epithet was in relation to kings. Ancient cultures, particularly Egyptian and Babylonian, described their kings as divine ‘images’. The idea was similar to that in connection with religious statues. Kings were considered divine representatives or ambassadors. They exercised the rule of the gods over the people. Genesis 1 appears to endorse this notion of the divine ambassador but it does so in a democratised fashion. According to the author, all people, not just kings, have been fashioned in the image of the one true God. Notice also that v.27 makes a point of including both male and female persons within the image of God.

Human beings are not the product of a defeated god’s blood; they are divine representatives, created to exercise God’s careful rule over the creation, to ensure that his interests are realised in the world.17

The service of God

There is another striking point made in these paragraphs. I noted earlier that the purpose of humanity according to Enuma elish (and other pagan myths) was to serve the gods with food offerings. In light of this, Genesis 1:29 may well have sounded very odd to ancient ears. Having urged men and women to exercise the divine rule over the earth, God then offers food to them:

Then God said, ‘I give you every seed-bearing plant on the face of the whole earth … they will be yours for food.’ (my emphasis)

God serves us. What a subversive thought this was in ancient times! It is a theme that reaches its climax in biblical tradition in the equally radical notion of Christ’s offering of himself for the sins of the world. What Genesis conveys metaphorically, Jesus would embody historically. But, of course, that goes beyond the scope of this piece.

The author of Genesis 1 would not have been aware of the assumptions that would be brought to his text years later.

Conclusion: Genesis and the search for meaning

I have argued in this paper that the author of Genesis 1 would not have been aware of the assumptions that would be brought to his text years later by six-day creationists and scientific materialists. He was not concerned with how the universe originated. Rather, he sought to answer the more urgent questions of antiquity:

- From whom did the creation originate?

- What is the nature of that creation?

- What place do men and women occupy in the creation?

I have referred above to the exposition of Genesis 1 by the 1st-century Jewish intellectual Philo of Alexandria. In the conclusion to this work On Creation he lists the five things the author intended to teach us in the opening chapter of Scripture:

- God has existed eternally (against the atheists, Philo says);

- God is one (against the polytheists);

- The creation came into being and is not eternal;

- There is one created universe not many;

- God’s good Providence originally fashioned and currently sustains and cares for the creation.

The one who embraces these five truths, says Philo, ‘will lead a life of bliss and blessedness, because he has a character moulded by the truths that piety and holiness enforce’ (On Creation 172). For Philo, in other words, Genesis 1 answers philosophical, existential and theological questions. It is not concerned with the physical mechanics of origins.

The French philosopher and Nobel Laureate, Albert Camus (1913-1960), once contrasted scientific truth with philosophical truth. The one was valuable, he said, but not worth dying for. The other was central and very much worth living and dying for: ‘I therefore conclude,’ he wrote, ‘that the meaning of life is the most urgent of questions.’18 I have argued above that Genesis 1 must be understood in just this context. In its highly literary form and against the backdrop of competing pagan claims the Bible’s opening chapter declares not a scientific truth of moderate importance but a bold answer to this ‘most urgent of questions.’

Dr John Dickson is Director of the Centre for Public Christianity and Honorary Associate of the Department of Ancient History at Macquarie University (Australia).

Footnotes

- Exodus 20:3-5 – You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself an idol in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below. You shall not bow down to them or worship them.

- Psalm 95:1,3-5 – Come, let us sing for joy to the LORD … For the LORD is the great God, the great King above all gods. In his hand are the depths of the earth, and the mountain peaks belong to him. The sea is his, for he made it, and his hands formed the dry land. Psalm 96:4b-5 – … great is the LORD and most worthy of praise; he is to be feared above all gods. For all the gods of the nations are idols, but the LORD made the heavens.

- See Hess R. S., “One Hundred Fifty Years of Comparative Studies on Genesis 1-11: An Overview,” in Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura (editors), “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11 (3-26). Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994.

- For the dates of the documents and inscriptions in question see the relevant chapters in ‘I Studied Inscriptions from Before the Flood’.

- The title comes from the opening words of the cuneiform text: “When on high (enuma elish) …” The texts of various Mesopotamian myths, including Enuma elish, can be found in Dalley, S. (trans.), Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Leading the charge with the theory that Genesis was deeply dependent on the Babylonian myths was Herman Gunkel’s monograph of 1895, Schöpfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit: Eine religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchung über Gen 1 und Ap Joh 12. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. For an abridged English translation of the relevant parts of Gunkel’s study see Anderson, B. W. (ed.). Creation and the Old Testament (Issues in Religion and Theology 6). Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984, 25-52.

- Standard introductions to this theme in scholarship are found in Sarna, N. M., Understanding Genesis. New York: Schocken Books, 1970; Kapelrud, A., “The mythological features of Genesis chapter I and the author’s intentions,” Vetus Testamentum vol. 24, no. 2, (1974) 178-186; Tsumura, D. T., “Genesis and Ancient Near Eastern Stories of Creation and Flood: an Introduction,” in “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11 (eds. Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura).Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994, 3-26. A vigorous attempt to rebut the ‘majority view’ espoused above is found in Kaiser W. C., “The literary form of Genesis 1-11,” in New Perspectives on the Old Testament (ed. J. Barton Payne). London: Word Books, 48-65.

- Apsu, Tiamat, Lahmu, Lahamu, Ansar, Kisar, Anu, Nudimmud, and Mummu.

- The name ‘Yahweh’ is represented in English Bibles by the word ‘Lord’, written in capital letters. This is rather unhelpful really because the word doesn’t mean ‘lord’ at all; it’s a personal name and was intended to be used as such.

- Only in the introduction to the next section, in chapter 2:4, does the author name this Creator-God as Yahweh elohim, the God named Yahweh. This is such a striking feature of the text that some scholars have proposed that chapters one and two were written by different authors. The first they call the elohist because he preferred the generic word ‘god’ or elohim, and the second they call the yahwist because he preferred God’s personal name. The phenomenon is far more easily explained, as above.

- His extraordinary account of the number 7 is found in On Creation 89-128.

- This insight corresponds to that of the first century Jewish author, Philo, as mentioned at 1.1.

- In fact, in Egypt, Amon-Re, the Sun-god, was said to rule the entire Egyptian pantheon, a collection of no fewer than 2000 deities.

- This same basic story, though in more detail, is narrated in Tablet 1 of the Babylonian Atra-Hasis Epic which dates about the middle of the second millennium BC. On this see Millard, A. R., “A New Babylonian ‘Genesis’ Story,” in “I Studied Inscriptions from before the Flood”: Ancient Near Eastern, Literary, and Linguistic Approaches to Genesis 1-11 (eds. Richard S. Hess and David Toshio Tsumura).Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1994, 114-128.

- The ancient practice of placating deities with food offerings derives from stories such as this.

- There are all sorts of philosophical suggestions about what it means to be made in the ‘image of God’. Some take the phrase as a reference to our critical faculties, others to our moral perception, still others take it to mean we possess a spirit just as God is a spirit. The historical analysis above, however, offers a more cogent interpretation.

- It’s precisely this logic that leads to the words added in v.26: “let them rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air” and so on. The point is reiterated in v.28: “God blessed them and said to them, ‘Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air and over every living creature that moves on the ground’.”

- Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus, trans. Justin O’Brien (New York: Vintage, 1960), 3-4.