Youth Resource

Are there good reasons to have faith in God’s existence?

Whilst we cannot ‘prove’ the existence of God, there are many good reasons, both rational and emotional, for belief in a divine being.

Videos

-

Behind the Life of Jesus: Is there a god?

John Dickson and Greg Clarke discuss whether there are things that might point us to belief in God.

Transcript

JOHN DICKSON: Hi, John Dickson here from the Life of Jesus. The purpose of this whole project is to explore the life of Jesus in its historical context, and it’s important in the documentary proper to maintain the secular, historical approach to the man from Nazareth. But there’s no question that the story of Jesus has had a profound impact on the history of the world’s art, politics, ethics, philosophy and so-on. There’s also no question that the Jesus story itself raises philosophical questions about the meaning of life and ethics. So, we want to go behind the life of Jesus and explore some of these more profound ideas, and I can’t think of anyone I’d rather chat to than my academic colleague Dr Greg Clarke.

Greg, obviously the first question that the Jesus story raises is about the existence of God. It’s kind of true, isn’t it, that lots of people throughout history have shared that belief in some great mind?

GREG CLARKE: That’s certainly got to be our starting point, hasn’t it, because most people in most cultures at most times in history have had some kind of belief in a divine being or beings; some kind of great mind or power that’s behind everything.

JOHN DICKSON: I find it fascinating actually, I mean here we are at a Buddhist temple, and the Buddha himself was practically an atheist – he didn’t want to believe in God – but within a couple of hundred years, mainstream Buddhism starts to reintroduce the notion of deities.

GREG CLARKE: Right, and there’s this natural kind of human instinct that takes over, to think that there is a God, so we’ve got to really see whether there is any question, anything to doubt in that presumption. So, it’s always going to be really difficult to disprove God, to prove that God doesn’t exist, I mean you can’t really prove a negative, so we’re left asking questions like ‘Is it possible for God to exist?’ or ‘Is it likely that God exists?’

JOHN DICKSON: I think a lot of people would accept that it’s possible, even hard-core sceptics would say that it’s possible, but they’d question you that it’s likely.

GREG CLARKE: You’re right, most people do think that it’s possible. Some people think that the fact that there’s evil and suffering in the world is enough to show that God could not exist; God couldn’t allow a world like this to exist. But most people even on that question are crying out to God; it makes them hungrier for God. It’s not a dis-proval of God’s existence, it makes you want to understand God better. So, we’re left really asking that question, ‘Is it likely that God exists?’ And I think it’s likely that God exists for a whole bunch of reasons. Let me just give you a few of them.

The first one is that God really is the best explanation for why there’s something here, rather than nothing. I mean, proposing that there’s an eternal being that is the reason for the universe actually makes a lot more sense that saying it just spontaneously, somehow, occurred – I mean that is just less rational. Secondly, I think that the kind of universe we see with its extraordinarily complex arrangements, its wonder, its beauty, its depth – you just don’t get those kinds of universes by chance. I mean there hasn’t really been enough time, even with processes like gradual evolution, for such a universe to have come about by chance – a universe that’s filled with intelligence, people like you and like me who can understand the universe – we just have an excess of intelligence, and it’s really hard to explain that unless you propose that there’s some mind behind it, rather than just mindless chance. Thirdly I think, when you look at the universe, it’s just the kind of place you’d expect to find if God is real, and it’s the kind of place you wouldn’t expect to find if there’s no god. I mean, things like human conscience – we have a sense of right and wrong, a sense that what we do matters – these things make more sense if there’s someone behind the universe to whom we are accountable. Things like our sense of meaning and purpose, I mean most human beings think that the world is meaningful rather than meaningless, and this draws us back to someone, some mind, who is generating the meaning.

JOHN DICKSON: But some would say that just evolved with us as a natural byproduct of our evolution.

GREG CLARKE: Well, there may be something to that, but the kind of things you find in the world and in human experience are the sort of things you don’t expect to find if the world is just mindless evolution; they’re the sort of things you do expect to find if there’s a god, and reason, behind it all. So, other things like the fact we have a fear of death and a sense of eternity, these are all things that point us back towards God, and I find when you add these things all together, there’s a great likelihood that God is real.

close -

Reasons for Faith in God

William Lane Craig on what faith is, and why there are good reasons to believe in the Christian God.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: Let’s talk about faith. I want to ask you, can you explain simply why you think it’s more likely that there is a god of some kind, than not?

WILLIAM LANE CRAIG: Yes. Let me say first what I think faith is. I think faith is trusting in that which we have good reason to think is true, so that faith and reason are not contrary to each other, but rather faith is trusting in something that we have good reason to think is true. And I think that the hypothesis that God exists explains a vast range of the data of human experience, such as: the origin of the universe at a point in the finite past; the applicability of mathematics to the physical world; the fine-tuning of the universe for intelligent, interactive life; the existence of a realm of objective moral values and duties; states of intentionality or consciousness in the world; the historical facts concerning the life, death and resurrection of Jesus; and finally I think that God can be personally known and experienced. And so, for all of those reasons, I think that the God hypothesis is a very powerful explanatory hypothesis, and therefore is much more likely to be true than the hypothesis that God does not exist.

SIMON SMART: Some of what you’re talking about there might lead someone to consider a god, and they might even become theists, but that’s some way from the Christian God. Why the Christian God, for you?

WILLIAM LANE CRAIG: Well you notice the first several points that I enumerated are consistent with any sort of monotheism. If these arguments are correct, they will serve to exclude atheism and agnosticism, as well as pantheistic religions that identify the world as divine. It gives us a transcendent creator and designer of the universe. So, it narrows down the fields of the world’s religions to the great monotheistic faiths, like Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Deism. Now to move beyond that I think we need to look at the historical person Jesus of Nazareth and what he claimed and taught. And my argument would be that Jesus’ claims to be the absolute revelation of God were vindicated by God raising him from the dead, and that therefore the historical credibility of the resurrection of Jesus vindicates his radical personal claims, shows that he was who he claimed to be, and thus serves to narrow down the field of monotheisms to Christian monotheism in particular.

close -

Longing for transcendence

Tom McLeish on what humanity’s desire for transcendence might tell us about the existence of God.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: What about transcendence? I want to ask you about that. Do you have a sense that people today long for something beyond the hard, material facts of life?

TOM MCLEISH: Yeah, I think they do, and I think that is significant. We’re people – I mean, one of the mystical wonders that this universe has [is] that we are part of the universe. I mean, I love the idea, I think Carl Sagan and others have talked about it, that we are the universe becoming aware of itself. Lawrence Krauss said that too – I think it’s a wonderful thing to say. And yet we, as people, as agents, we yearn for something more. We talked before about physicists being no-smoke-without-fire people – if there’s gravity around, there’s a mass; if there’s an electric field in the air, there’s a charge somewhere making it. And there are very few things that humans desire that don’t have an object of that desire. You know, we get thirsty, well there’s water and so forth. So the fact that we’re thirsty for something beyond, for a deeper meaning, maybe for a person, does indicate that it’s worth looking for that person or being open to their existence.

SIMON SMART: Yes, and you’re convinced that Christianity has something to say to those longings.

TOM MCLEISH: I’m convinced that Christianity has something to say to those longings, yes. And one of the reasons [is] I tend to see Christianity as an anti-religion. You see, some people say to me: “How do you make your mind up between all these religions? There are thousands of them. Equally well one could be true or the other.” But there’s something in me that wants to say: well actually the reason – one of the reasons – that I was attracted to Christianity is because in some senses it’s sort of anti-religion. That sounds funny, doesn’t it, but the dynamic is opposite. You see, many religions start from this, what you called it, transcendence – there’s something beyond we’ve got to get to. And they have all sorts of recipes for the way in which we get to it, or maybe they respond to this fish-out-of-waterness we talked about – we’re not friends with nature, we’re frightened of it, it’s painful – and that’s where science comes in. And there’s all sorts of things we can do to mend that relationship.

Well, actually, the refreshing thing, the logically refreshing thing, that I’ve found about Christianity, is it recognises there’s nothing we can do. If we could imagine mending a broken relationship with a creating God, from whom we’ve walked away – there’s nothing we can do. But the great thing about Christianity is that actually, God does all that. That’s what the incarnation is about – it’s the self-emptying, it’s not denying the pain, it’s entering into the pain, and saying this is how much I love you. So, that’s sort of anti-religion: not us reaching up, God coming down. That’s got to be right. So yes, that to me helps make sense of the Christian faith.

close -

On what faith is (and isn’t)

Alister McGrath reflects on how it’s possible to live an authentic life.

Transcript

I think when I was an atheist, I assumed faith was simply believing something that was clearly not true and running away from the evidence. But I was very young then, and the world seems very simple to a 16-year-old.

Nowadays, I would say something like this: faith is the irreducible condition of humanity. To live authentic lives, whether you’re an atheist or whatever, you have to believe certain things you cannot prove to be true. And therefore it’s not about proving things, it’s about saying, here are good reasons for thinking this is right. It’s about warranted belief. It’s not about, in effect, arbitrary decisions; it’s saying, I can’t prove this to be true, but everything seems to point in this direction.

So for me, faith is a reasonable way of looking at the world, which makes sense of it – recognising these are such big questions we cannot hope to prove these things, but nonetheless saying, this makes sense and (perhaps more importantly) this is a way of thinking, a way of seeing things that is to be trusted and is to be inhabited.

What I mean by that is, the world of faith is a landscape, and you step into it and you say, I could live here. This makes so much sense, it’s so engaging, so exciting, you’ll want to go in and be there.

close -

On things we cannot prove

Alister McGrath outlines the human predicament, whether you’re an atheist or a religious believer.

Transcript

I think many people, particularly from the New Atheism, would say, well, God is just an unevidenced entity that’s proposed for the world. In other words, it’s like some teapot orbiting the planet Jupiter, or something like that. There’s no evidence for that, so why believe in that.

I think it’s very interesting to note how this whole idea seems to assume that God is an object within the world. And of course, if you’re a religious believer you’ll just say, well, that’s not what I believe at all. It’s much more about God being the ground of our being, the framework within which the universe is set. It’s something much greater than that – it’s not so much an object within the world, it is something that gives the world meaning.

In my own case, actually, I believe in God primarily, I think, because God gives stability to meaning and value. In other words, it’s not just believing that there is a God, it’s that if there isn’t a God, then we can’t give any stability to ideas of what is good, what is meaningful. And these are extremely important things for human life.

Let’s take this a stage further. I mean I cannot prove that things called human rights exist. I don’t think anybody listening to me now would say, well, that’s a reason for giving up on human rights. I cannot prove what is good – but that doesn’t stop me trying to be good, even though I can’t prove what the good is.

The reality, which I think many people have failed to grasp, is that the human predicament is such that we cannot prove the most ultimate beliefs on which life is based. Whether you’re an atheist or a religious person or a politician, you end up believing things you cannot prove. And that’s just the way things are. And I have to say I’m very, very sceptical about these simplistic arguments that we only believe what we can prove. It’s not right. We can prove shallow truths. But the deep truths which give life meaning and value, they lie beyond proof.

close

Articles

-

Reason has its place, but the human heart yearns for awe

Can the atheist worldview account for the longings of the human heart?

-

Christmas: too good to be true?

Is it merely a human fantasy that lies at the heart of the original Christmas event?

-

The Joy of Creation

Justine Toh marvels at what goes into the making of the perfect violin.

-

God: an illusion, or just invisible?

Richard Shumack asks if it is even possible to prove God according to scientific criteria.

-

Irrational Unbelief

Simon Smart responds to an article suggesting religious belief is evidence of irrational thinking.

Engage

- Set up a Tug for Truth diagram on the board at the front of the classroom, with the question ‘Does God exist?’

a

- Discuss in pairs about whether you have an opinion on this question

- Add post-it notes to the diagram for:

- Evidence / support for the ‘Yes’ position

- Evidence / support for the ‘No’ position

- Questions about the tug of war itself (such as ‘what if’ questions)

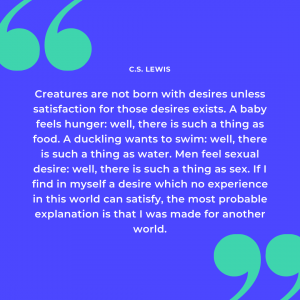

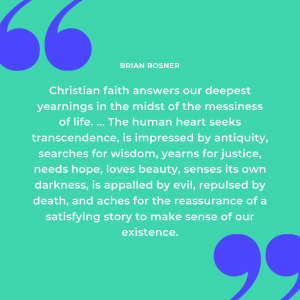

- Read the following quotes, and choose one that stands out to you. With another student, discuss why you chose that quote, and what your opinion about that quote is.

b

- Write down your one-sentence definition of ‘faith’.

Understand & Evaluate

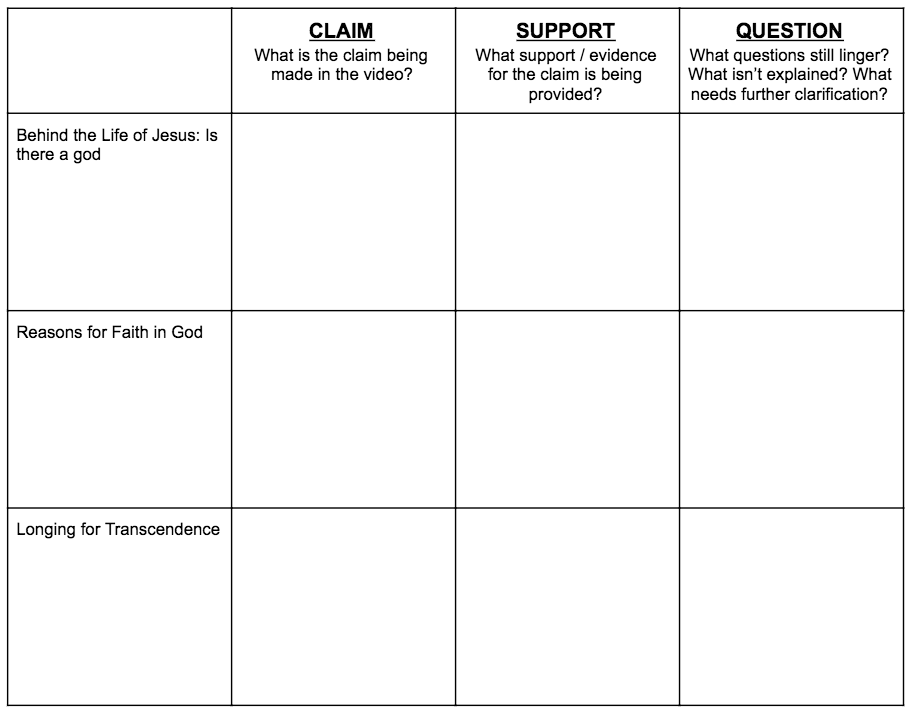

- Watch Behind the Life of Jesus: Is there a god?, Reasons for Faith in God, and Longing for Transcendence. Complete this ‘Claim, Support, Question’ table for each of the three videos.

- In small groups, read one of the articles.

- Highlight phrases / sentences that stand out to you

- Underline any parts you find confusing

- Come up with a summary sentence for the article

- Answer this question: What does this article add to the discussion of whether there are good reasons to have faith in God’s existence?

- Watch On what faith is and isn’t. Discuss your views on McGrath’s definition of faith, as well as the definition given by William Lane Craig: “Faith is trusting in something that we have good reason to think is true.”

- Think back to the definition of ‘faith’ that you wrote at the beginning of the class. After hearing McGrath and Lane Craig’s definitions, is there anything you would change about your definition? Why or why not?

Bible Focus

- Read Hebrews 11:1. In your own words, summarise the writer’s definition of faith, and compare it with your own definition and those of McGrath and Lane Craig.

- Read Psalm 19:1-4 and Psalm 42:1-2a. What support, both rational and emotional, might these verses give for faith in the existence of God?

Apply

- Hold a class debate on the topic: “There are good reasons to have faith in God’s existence”. (Split into affirmative and negative teams).

- Read the following quotes and write a personal reflection on whether or not you believe them to be true.

c

- H.G. Wells said, “If there is no God, nothing matters. If there is a God, nothing else matters.” How important do you personally think it is to explore the existence of God? How might your life change if you were confident that God existed?

- Return to the Tug for Truth from the beginning and add more post-it notes to the diagram. Discuss as a class which way you now lean, and whether that has changed since you began exploring this topic.

Extend

- Watch this clip from Alister McGrath: On things we cannot prove. Write a short letter to McGrath sharing some of your thoughts and questions in response to what he says in the video.