Youth Resource

Human Dignity: The Present and Future

The videos, articles, extracts, and suggested activities in this Classroom Resource examine the extent to which the Christian notion that humanity is created in the ‘image of God’ still impacts society today, and what the implications might be if this foundation for human dignity is gradually forgotten.

You may also want to include this segment from the For the Love of God documentary in this lesson, and/or incorporate ideas from this Classroom Resource from the For the Love of God series. There is some overlap between the concepts in that Classroom Resource and this one.

You may also want to do the first lesson in this series (Human Dignity: The Foundation) before this one.

Videos

-

On the future of human rights

Nick Spencer reflects on what is (and isn’t) likely to happen as Western culture drifts away from Christianity.

Transcript

There is some sense that this Christian understanding of human dignity – inviolable human dignity – and what it means might be being lost.

There are two really important caveats here. The first is that it’s very easy to get apocalyptic about this: “oh, my goodness me, unless we all turn back to the church next week we’re going to hell in a hand cart”. That is not what I am saying. The second point is that I’m talking about, if you like, deep sea intellectual currents. These things change over centuries, not decades – let alone years or so. So if we see any change in Western culture because of a drifting away from Christianity, it won’t be within my lifetime. And I’m still kind of young and vigorous (I like to think, anyway).

So they are very important caveats. But in things such as … and you tend to see it around the beginning and end of life debates – and I don’t particularly want to gravitate to those, but that’s kind of where you see them. In the idea that the human life can be determined by the value that the human puts on that life – or in the case of the very young and the unborn, that somebody else puts on that life – you are moving away from the idea that that life is valuable irrespective of what you think about it.

Now I don’t see that leading towards a gas chamber – that is emphatically not what I’m saying here. But it’s always worth attending to the way in which we engage with those who are at the periphery or perhaps the weakest points of our society, those who are not able to defend themselves, or articulate their own worth. And that, I think, probably in the longer term is my greatest concern about drifting away from this Christian conception of the human.

close -

On forgetting why humans are precious

Francis Spufford explains what’s fundamentally unreasonable about Christianity.

Transcript

I think self-understanding is in danger of being lost if Christianity fades out of the picture as the, kind of, the known source of some of these things. I think that people thrive best when they know what the historical roots of their own ideas are. In a way, it would be just the kind of perverse gift to the world that Christianity has specialised in giving, if we left you with a bunch of ideas about human rights and left you thinking, ooh, it’s those Christians that are the enemy of human rights, but that’s actually not true.

I think the danger is that if the connection of those ideas to their original source is obscured, then part of the kind of the armoury of means for defending those ideas has gone as well. Christianity is fundamentally unreasonable in its attachment to human love, equality, and respect. We do it because we believe it’s right and we’re told it’s right. We don’t in fact have philosophical justification all the way down; beyond a certain point, we do it because we’re told people are precious. And then we make the experiment of looking around and it doesn’t kind of seem that they are precious, actually.

But in purely abstract terms it’s very hard to defend, rigorously, the proposition that you should always treat people with respect and always treat them as if they have infinite value. I mean, prove that. Perhaps they don’t have infinite value by the ordinary utilitarian calculus of the world – in which case, at the very least, Christianity is in the business of providing us with a potent “as if”, behave “as if” people had infinite value. We’re the wild-eyed fanatics who want to keep your minds on that point. We want you to go on remembering that people have infinite value. We think it’s because God said so – but you can ignore that part if you want.

close -

On the foundation of morality

John Lennox describes what happens when you accept (or reject) the idea that humans are made in God’s image.

Transcript

The biblical claim that every man and woman is made in the image of God is regarded by many people, actually, as the foundation of morality. If we reject the transcendent dimension to morality, we’re left to discover a base for ethics within the world – down here, in there – and so we’re going to find it where? We’re going to find it either in genetics, or in the development and evolution of society and so on. But that leads very rapidly to a subjectivism.

I mean a classic example is Darwin, who was a kindly man with a big beard. And he studied ants and said, well there’s a basis for altruism. But his contemporary Spencer looked at the same nature and said it’s red in tooth and claw, and talked about the survival of the fittest. Now both of those theories have been tragically – particularly the second – applied in ethics. And I think we’re seeing, in Europe particularly, the result of ignoring the Genesis story and therefore trying to get some sort of ethical foundations by moving away from the human to the animal.

Whereas if we look at the human and what’s said about human beings – “made in the image of God” – what does that mean? Well it means first of all that they are rational. God is revealed as personal in the Bible. It also gives them infinite dignity and value. And of course our values are crucially tied to our ethical systems. And I recall once being in Siberia and talking about these things – for the very first time by the way, in a lecture, first time in 75 years that had been allowed – in the elite university in Novosibirsk, and I said if I took that one statement, that human beings were made in the image of God, I wouldn’t murder one of you let alone the 70 million that Stalin did. And it was most interesting to watch, I got a standing ovation – it was very moving as they all simply stood. They’d realised the colossal impact of that statement. So I think it’s central to all ethical systems that are meaningful. And we neglect it at our peril, because we ultimately end up by ethics being virtually purely subjective.

close

Articles

-

Christianity is still the foundation of our most treasured convictions

Simon Smart traces the roots of the “inalienable dignity” of the human person to the Easter story.

-

How do we make human rights a reality?

On the anniversary of the proclamation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Natasha Moore asks: How are we doing?

-

Surprised by Peter Singer (Extract)

Sarah Irving-Stonebraker on human value, philosophy, and her surprising journey from atheism to Christian faith.

-

Why we need the Christmas story

What does the baby in the drain have to do with the baby in the manger?

Engage

- Using Canva, create two photo collages:

- One featuring examples in our society of people being treated as inherently valuable

- One featuring examples in our society of where human value is undermined

- In an article in The Conversation titled Why human rights should guide responses to the global pandemic, Sandra Liebenberg argues that “The goal of all response measures [to the pandemic] should be to create an environment in which all can live in dignity without excessive inequalities on grounds of race, gender, and socio-economic status.”

- Do you agree with this statement? Why or why not?

- Thinking of what you know of your country’s response to COVID-19, make a list of examples of how you think this has been done well, and another list of how it has been done poorly.

- Mark on the following scale to what extent you agree or disagree with this statement: Human rights are likely to suffer as society loses touch with the biblical teaching about the inherent dignity of all people.

Understand & Evaluate

- In small groups, watch the videos On the future of human rights; On forgetting why humans are precious; and On the foundation of morality and answer the following questions:

- Why is the person in this video concerned about society drifting away from the Christian conception of what it means to be human?

- To what extent do you agree with what they are saying?

- How might someone who isn’t a Christian counter their argument?

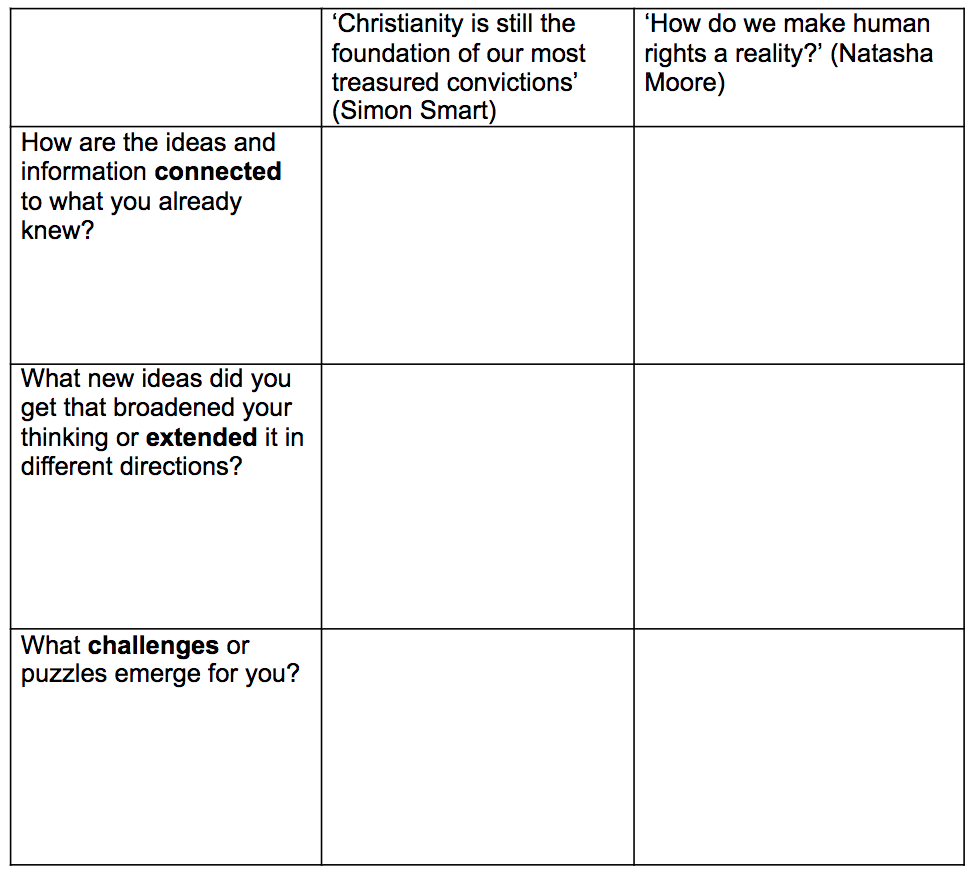

- Read the articles Christianity is still the foundation of our most treasured convictions and How do we make human rights a reality and complete this Connect-Extend-Challenge table for the articles.

- Simon and Natasha both quote Australian philosopher Raimond Gaita in their articles. What is striking about Gaita’s words, especially considering the fact that he is not a believer himself?

- Read the extract from the CPX podcast episode with Sarah Irving-Stonebraker titled Surprised by Peter Singer and complete the following activities:

- Write down something that stands out to you from Sarah’s story, and a question you would like to ask her

- Draft an email to Sarah in response to what you have read of this interview

Bible Focus

Read James 3:9-10 and 1 John 3:16-18.

- What do these passages say about how we should and shouldn’t treat other people?

- What reason is given in each of these passages for how we should treat others?

- Which of these passages do you find most compelling, and why?

Apply

- Hold a debate as a class on the question: Can universal human rights for all people continue without the notion that human beings are created in the ‘image of God’?

- Do the 3, 2, 1 Reflection Thinking Routine to reflect on this lesson. Write down:

- Three things you have learnt

- Two questions you still have

- One challenge you face

Extend

- Read Simon Smart’s article Why we need the Christmas story, and write a letter to the editor in response to his piece.