I know what I would smell like, cooked. The nurse even joked about BBQ. Intellectually, I knew that getting my face lasered would burn off those obvious (to me) age spots, but the sensory experience was something else. It’s not that I smelt bad. I just felt like a slab of meat.

Which I am. Human life is fleshly, although we forget. Apparently, you can open an unlimited number of tabs on your internet browser (except for Apple’s Safari, which cuts you off at a stingy 500). It’s a metaphor for online life, of infinite possibility. Also a poor reminder that real, embodied life comes with hard limits. But giving birth, the slip of a dentist’s drill, a long illness: all these jog our memory. We’re bodies who suffer, lust, and hunger and who will even aim bright, burning lasers at our faces in petty revolt against “the way of all flesh”: death.

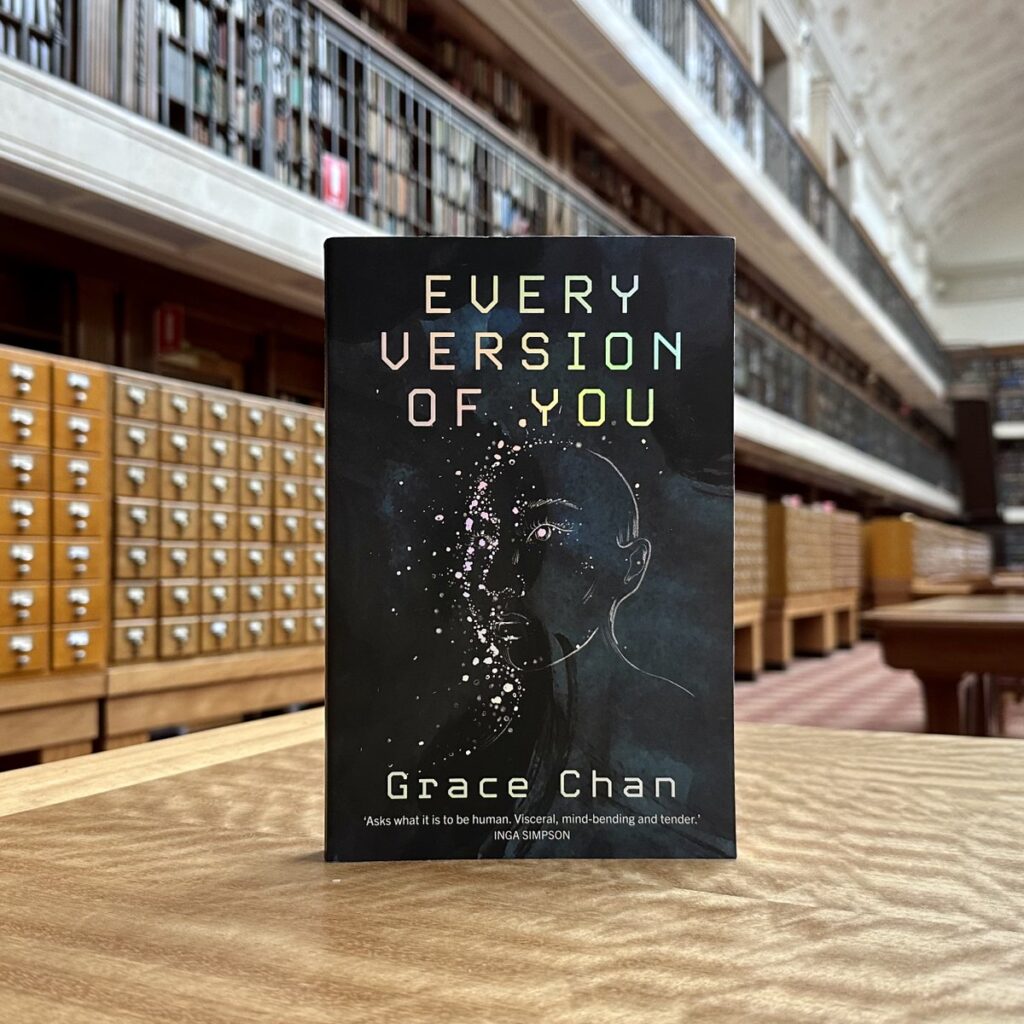

What if we could be free of all that? Forget the flesh and its frailties, or even the need for sleep. Immortality beckons. Not in a heavenly afterlife promised by traditional religions, but in the tech marvel of Gaia, a digital paradise to which humans can be uploaded – indefinitely. That’s the half-dream, half-nightmare premise of Grace Chan’s speculative novel Every Version of You.

Here’s the set-up: it’s the 2080s. Melbourne’s Yarra has long dried up. AUKUS apparently soured early mid-century: the U.S. bombed us back in 2041. Ecologically, earth is spent. Spotting a real live possum is a shock, fresh produce a distant memory. Extreme UV radiation is the norm: a ten-minute walk outside without bulky, protective clothing could laser your skin on the cheap.

Everyone has a ReVision: augmented reality headgear that’s kind of like Google Glass, except a commercial hit. And courtesy of Matrix-style pods, people lie smothered in goo that transmits electrical signals through their shaven heads, so everyone (but the poor) can enjoy a digital simulation of our world that’s fast improving on the original. It’s as easy as plug and play.

Except Gaia doesn’t do smell very well. While in Gaia, Tao-Yi, Chan’s protagonist, buries her nose in boyfriend Navin’s neck, but there’s no trace of his scent. He’s unbothered – in fact, Navin is keen to Upload to Gaia forever, since digital immortality will liberate him from his chronic kidney condition. You can’t suffer if you’re a being of bits and bytes. Tao-Yi has misgivings, but Navin becomes an early adopter of the Great Uploading. More and more of humanity joins him in the cloud.

Whether they remain human is debateable. The Uploaded become as expansive and infinite as the internet itself, “multitasking in a way that no original human can”. Imagine having endless bandwidth to go down infinite rabbit holes of any and every passing interest, and bringing entire digital worlds into existence. Being all-powerful and all-knowing has typically been a God thing. In Every Version of You, it’s on offer for the likes of Uploaded Navin, “a demi-god of the new age”, as Tao-Yi calls him.

Gaia might be another remixed spin-off: it reimagines heaven for 21st century sceptics.

In Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, the American writer Tara Isabella Burton scans the habits of the “spiritual but not religious” generation who are reinventing religion for themselves. They’re seeking meaning and purpose – the typical domain of religion – in yoga, astrology, Soul Cycle, even Dungeons & Dragons. This is faith “remixed”, says Burton: religion reconstituted, blended into something new.

Every Version of You’s Gaia might be another remixed spin-off: it reimagines heaven for 21st century sceptics. Religion, say, for Silicon Valley atheists.

The parallels are unavoidable. “Here in Gaia,” Chan writes, the formerly frail Navin “doesn’t grow short of breath”. Sounds like a remixed line from the biblical prophet Isaiah: “those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.”

Other references are more direct. Uploading, Tao-Yi gets, was Navin’s “salvation”. Later, she feels “sinful” – not for eating chocolate, as we might imagine, but for smelling his t-shirt back on earth. New religions create new heretics.

Including the “left-behind nobodies”: those who, for various reasons, decide against Uploading to remain on earth. When I imagine myself into Every Version of You’s thought experiment, one that swaps embodied life for a disembodied existence, I reckon I’d be a Remainer too. Even if it’s weird to be counted among the other weirdo dissidents refusing to enter digital heaven.

But maybe Remainers like me, and possibly author Grace Chan, (and maybe you?) are true believers in something else: the significance and value of bodily life. For us, Zuckerberg’s metaverse and any other iterations of digital second-life can float off into the ether. Meatspace is more our jam.

Justine Toh is a Senior Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity and the author of Achievement Addiction.