Youth Resource

Is the Bible’s account of creation compatible with science?

There are a range of views within Christianity by people who take the Bible seriously with regards to the early chapters of Genesis, and thus this can sometimes be a controversial topic. Without advocating one particular view, this activity aims to show that it is possible to take the Biblical account of creation and modern science seriously, as a close reading of Genesis 1 shows that it is not in conflict with scientific explanations about how the world and life were created.

Videos

-

Reading the Genesis creation accounts (Part 1)

John Dickson on how the genre of Genesis 1 affects how we should read it.

Transcript

GREG CLARKE: The beginning of the book of Genesis has become one of the most talked about parts of the Bible, even amongst some scientists. But how should we understand this account of the beginnings of the universe? What part do literature and history have in a proper understanding of the text? I put these questions to John Dickson who is a biblical historian, a Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Ancient History at Macquarie University, and my co-director here at the Centre for Public Christianity.

There’s a lot of really heated discussion around this question of the origins of life, creation, and especially the question of how we should interpret Genesis Chapter 1. Why, John, is this such an emotional issue for people?

JOHN DICKSON: Well, on the one hand, for many people, it’s a case of commitment to the Bible. If you take the Bible seriously, the Bible says the world was created in six days, and that’s it, so you’re either faithful or you’re not faithful to it. On the other hand, you’ve got sceptics like Richard Dawkins who think the whole thing is proof that the whole of Christianity is ridiculous, because the scientific evidence is overwhelming, they say, that the earth is very old and that it certainly wasn’t made in six days. So biblical faithfulness on the one hand, scientific integrity on the other, and they appear to be clashing.

GREG CLARKE: Some people would say that things like the very existence of dinosaurs, the age of the earth (that scientists know it’s a very old earth now) – these things just write the Bible out of the equation, it has nothing to say to us on the origins of life?

JOHN DICKSON: That’s exactly what someone like Richard Dawkins says in his latest book. But I think it misunderstands the basic genre of the text of Genesis, and it seems to me both six-day creationists and the sceptics are reading Genesis 1 the same way – they’re reading literalistically. And I actually draw a distinction between literalistic and literal. A literal interpretation (which is my own interpretation) says, “What was the author actually trying to convey through the literary methods available to him?” and a literalistic approach to Genesis says, “Well, I’m not so interested in what the author intended to say, what is actually said? What do the words actually say?” and they don’t worry about whether there’s any metaphor or whatever. So it’s a genre question for me.

GREG CLARKE: Ok, so genre seems to emphasise the purposes for which this literature might be written?

JOHN DICKSON: It does. It’s like a parable, you know, when you come across a parable in the New Testament you know what its intention is. It may or may not be a true story – say, the Parable of the Good Samaritan – it may or may not have actually happened, but that’s not the point of the story. Or when you come to the book of Revelation, there’s plenty of different images of beasts coming up out of the water and so-on, Jesus returning to earth riding a white horse. The point isn’t that these things will happen in that concrete way – they’re describing something using that metaphor. And I think, to read Revelation and the parable literally is sensitive to the original intention; to read it literalistically would say the Parable of the Good Samaritan actually happened, or, Jesus will actually come riding on a horse. And I think when you turn to Genesis 1, it’s clear we’re not dealing with historical prose. Most scholars are comfortable saying what we have in Genesis 1 isn’t like what you have in Genesis 13, for instance, where it’s more historical prose.

GREG CLARKE: What kinds of literary elements do you find in Genesis 1 that make you think that?

JOHN DICKSON: Well, the things that convince most scholars that we’re dealing with a highly literary, artistic form, are things like parallelism, rhythm, and number symbolism. Number symbolism especially, for instance, the opening sentence of Genesis 1 is seven words. The second sentence is 14 words. Immediately we’re sort of in the space of seven. Anyone who knows the Bible knows that the number 7 is the number symbolising perfection, and when you spot that you notice all sorts of things like the word “heaven”, the one half of the created order, appears 21 times in Genesis 1; the word “earth” 21 times. So multiples of seven. Phrases like “and God saw that it was good” occur seven times, and of course the whole thing is created around seven days, seven stages. So, it should be quite clear to an ancient reader, that the author of Genesis, whatever his actual views of physical origins, is trying to convey something through the artistry of literature.

GREG CLARKE: Now some people say that that literary understanding of Genesis is just a result of Christians having to rethink their reading of it, and that surely Christians in the past, the Church fathers and so-forth, didn’t think this way.

JOHN DICKSON: Yeah, well, Richard Dawkins says that, and it’s an easy target for him to say, “No, no, no, the only true interpretation of Genesis 1 is this literalistic one, and you shouldn’t fudge it by picking and choosing how you interpret it.” But actually, that misses a pretty significant movement of Biblical interpretation going right back to the first century. So, the Jewish scholar of the first century, Philo of Alexandria, interpreted Genesis 1 in a non-concrete way, in a metaphorical way. And a number of the early church fathers did, so Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Augustine, St Ambrose of Milan, and then right to the Venerable Bede and Thomas Aquinas all interpreted Genesis 1 not in a literalistic way, but in a sort of more symbolic, theological way. And this is long before the rise of science, before science was a “problem” for a literalistic interpretation of Genesis.

close -

Reading the Genesis creation accounts (Part 2)

John Dickson on how the genre of Genesis 1 affects how we should read it.

Transcript

GREG CLARKE: Ok, so the literary reading is not a novel and modern approach, but if we take that as our understanding of how Genesis should be read, what kinds of purposes might an author have for writing that way about things like the origins of the world?

JOHN DICKSON: Well, we’re really greatly helped by a number of discoveries that occurred in the 19th century, actually, virtually the same year that Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species was published. We discovered some tablets in the Middle East that gave us an account of creation very similar to the Genesis account, but it came from Babylonians. It’s called Enuma Elish. An on these tablets was written a story – on seven tablets, actually, it’s a seven-stage story, which is interesting. But the opening lines of Enuma Elish say that before the origins of the world there was a watery chaos – now that’s interesting, because that’s the same thing that you have in Genesis.

GREG CLARKE: It rings bells for those who know of the spirit of God hovering over the waters.

JOHN DICKSON: It does. And so a number of scholars immediately thought, “Aha! Genesis has just borrowed Enuma Elish.” And then as the dust settled, they began to find that actually the differences between Genesis 1 and Enuma Elish are profound, very striking, in fact contrary. And the standard view now is that Genesis is a deliberate critique of other views of the nature of the universe. So, there are all sorts of things you find in Enuma Elish that Genesis contradicts. The form is very similar, but it’s kind of a parody, or a subversion, of ancient views of God and of humanity.

GREG CLARKE: Can you give us a few examples?

JOHN DICKSON: Yeah, well I’ve already said the similarity of coming over seven stages. The order of creation is the same in Enuma Elish and Genesis. And human beings are created in the sixth stage: sixth day in Genesis, sixth tablet in Enuma Elish. However, the basic theme of Enuma Elish in terms of its view of creation, is that creation is the result of multiple gods – I think nine gods are mentioned in the opening lines of Enuma Elish. But you come to Genesis and there’s one God – absolutely solo. And to any ancient reader who comes to Genesis, they know what’s being said here. The creation is not the result of multiple gods, but one God.

I think the other thing is the coherence of creation. In Enuma Elish the creation is sort of this haphazard result of a warfare amongst the gods, but in Genesis 1 God speaks and it is, God speaks and it is – very coherent and ordered. And this is very much the Jewish-Christian view of creation, that it isn’t just this superstitious, capricious, haphazard universe, it’s an ordered work of art.

GREG CLARKE: One of the hottest questions today is the place of human beings in the world, are they special? How does the Genesis 1 account compare with other ancient creation accounts on that question?

JOHN DICKSON: This is probably its most striking point of contrast. In Enuma Elish, for example, human beings are created out of the leftovers of the vanquished gods, and that doesn’t give us a very high view of humanity, and in any case, the only reason human beings are created is because the vanquished gods were in prison having to serve the victorious gods food all day, and they begged, “Oh, you’ve got to create something else to do this, we’re gods after all”, and so they created humans, in other words, to serve the gods. And then Genesis comes along and says, yes, human beings are created in the sixth stage, just like in Enuma Elish, however, they’re not created as an afterthought, they’re created in the “image of God” to rule over creation. And then God says, “I give you all seed-bearing plants.” When you contrast that with the pagan view that humans were created to give the foods to the gods, we have a turning upside down of ancient views of humanity. And this really gave rise to the strong western view that humanity is special, is a high being, that God really cares for and has intentions for.

GREG CLARKE: Does this understanding of Genesis 1 commit you to any particular view of origins?

JOHN DICKSON: Not a scientific view of origins, I mean, reading Genesis this way, as most scholars do, really doesn’t have much to say about how the creation came about. So, I think you could be a committed six-day creationist and still admit that this is the point of the Genesis 1 narrative.

GREG CLARKE: One final question, many people look to Genesis for answers to significant questions about life, but what questions is Genesis 1 answering?

JOHN DICKSON: Well I think the first thing to say is that it isn’t answering the question of the mechanics of creation. It’s so anachronistic to think that a text written thousands of years ago could possibly have been interested in the very modern question of the mechanics of the creation of the world. It’s actually asking the universal questions: What is God actually like? What is this creation like – is it capricious or good? (Genesis says that it’s good). And then I think ultimately, what is our place in the universe and before God and in connection with other creatures? And to all of these profound, universal, timeless questions, Genesis gives an amazing set of answers.

close -

Seven days that divide the world

John Lennox explains how he understands the Genesis creation accounts.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: John, I want to talk to you about the book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible. You’ve done a bit of thinking about this – you’ve got a book out on it, Seven Days that Divide the World. How do you reconcile the description you find in the book of Genesis with what you know as a scientist?

JOHN LENNOX: Well you’ll be amused to know, and I must confess it Simon, that I come from the city in Northern Ireland called Armagh, where Archbishop Usher was, who calculated the date of creation as 4004 BC. And you will remember that he said he reckoned that Adam was created at about 9 o’clock in the morning, but he apologised in a letter to Cambridge’s Vice-Chancellor that he couldn’t be more accurate than that.

SIMON SMART: Well, what do you do with that?

JOHN LENNOX: Well we start with, “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth”. And then there is a sequence of six days, and each of them begins with the phrase “and God said”, “and God said”, “and God said” – and then after those six days of creation activity God rests on the seventh day.

Now, just looking at that, the first thing to notice is that there is a literary pattern. One would logically conclude, I think, prima facie, that Day One begins with “and God said”. And that means that “in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” is not talking about Day One, but is prior to Day One.

Now instantly, you see, that removes the difficulty with people saying that the Bible insists the earth is young. The Bible doesn’t insist the earth is young! It says that in the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth – it doesn’t say what time that was at – and then it gives a sequence of creative acts of God, which we can discuss separately. And interestingly enough, when you check with the Hebrew scholars, they tell you that the tense changes from verses 1 and 2 to verse 3, and the tense that’s used in verses 1 and 2 is normally the tense used to describe something that happens prior to the sequence that’s following. So there’s corroboration from both logic and grammar that perhaps this text is a little bit more sophisticated than people think it is.

SIMON SMART: You would take the approach then that there’s a lot more going on in this text from a literary basis, which would indicate that it doesn’t demand a literal six days?

JOHN LENNOX: Well, we have to look at this word “literal”. Think of this statement – Jesus said, “I am the door”. Well, we don’t understand that to mean that he was a door made of wood or metal or plastic. It’s because of our experience of doors made of wood, metal, and plastic, though, that we know it’s meant at a metaphorical level. But – careful – because the metaphor is a metaphor for something real. Jesus is a real door, not a literal door – or you might say he is a literal door at a different level. That’s why I find the word “literal” actually a bit unfortunate, and it’s why many people use the word “literalistic” to describe that absolutely basic literal level.

Now, pursuing that, I would want to argue that the word “day” in Genesis 1 and 2 has four different meanings – and all of them are literal. Do you want me to prove that to you?

SIMON SMART: Sure.

JOHN LENNOX: Well, take the first. “And God called the light day and the darkness he called night.” How long is that? Well, it’s certainly not 24 hours, because the text is drawing your attention to the distinction between day and night. So that’s the first meaning, it’s the hours of daylight – roughly twelve at the equator.

OK, come to the next one. “And there was evening and morning, one day”. Now I know scholars discuss that a little bit, but it seems the consensus is generally that this is the Hebrew way of describing a full 24-hour period. So that’s meaning number two.

Then we read, “God rested on the seventh day”. But there’s no formula, “and there was evening and morning, Day Seven”. Now that’s interesting, as Augustine pointed out centuries ago. And if you ask people theologically what that means, there was a sequence of creative acts and God rested. When did he start creating again? He didn’t – the rest is still going on. So that absence of the formula actually opens up a possibility into a theological dimension. So that’s three meanings.

Then you come to Chapter 2 and the end of that first section of Genesis, where it says, “when God created the heavens and the Earth” – but actually the word “when”, it’s actually “in the day” God created. Now, that doesn’t mean Tuesday or Monday…no, it means “when”! Just as, if I said to you, “In my young day at Cambridge, we had to wear gowns after dark”, you wouldn’t say, “Do you mean Sunday or Tuesday?” No, it means a particular period of time.

Now, here’s a compressed text. It uses the word “day” quite often. It uses it with arguably four different meanings – and that’s an indicator to me that here we must be very careful before we jump to conclusions. It opens up more logical possibilities.

The idea would then possibly be that God speaks, Day One: “Let there be light”. And then that settles down. And then God speaks again. When does he speak again? Well, presumably, after the first time. But it seems to be that the Scripture allows the possibility that there’s an enormous space between the days – that is, they are the points, so to speak, where God inputs a new level of energy and information.

Now the interesting thing about that is, that would mean that, so far as any evidence was left in the scientific investigation of the universe, we might expect to find the sudden appearance of new levels of complexity – which is what we do find. And I personally see no compromise with the authority of Scripture in this. But it is a big subject, and one needs to have much more time to unpack it.

SIMON SMART: Well, let’s look at Genesis itself then, and – putting aside some of these arguments – what are the key messages of the early chapters of Genesis, and why do they matter?

JOHN LENNOX: Well I like your question, because the sad thing is, with many people they think that once they have come to a satisfactory (for them) understanding of the days of Genesis, they’ve understood Genesis. They haven’t begun to understand Genesis! Genesis is utterly foundational to the theistic, the Judeo-Christian worldview.

It tells us, first of all, that there was a beginning. It tells us that God was the beginner of everything – he is eternal. It tells us that God is not a force, He’s a person. And it begins to build up a picture of the universe, step by step. It tells us that God had a goal of building up the universe – his goal was to have human beings in it, and they are special. How are they special? They’re made in God’s image.

The Bible is very careful to explain that, although the heavens showed the glory of God, they weren’t made in his image. Human beings were, so they’re the pinnacle of his creation. That immediately puts a stamp on their value. And it tells us he created them equal, male and female. That is an enormously important thing for the value of men and women in the contemporary world.

We read of sin entering into the world; we read of the damage it does, of the fracture between God and human beings. And because of that, we begin to understand why the way back must include where the fracture occurred. The fracture occurred because people couldn’t trust God, so they have to learn to trust God again – and how that’s brought about.

It’s those things that are vastly important. Much more important than the days of Genesis, if I might say so, because I notice that they are not mentioned in the New Testament at all.

close -

Reading Genesis in its context

Professor John Walton on the importance of paying attention to the original context when reading Genesis 1.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: I want to talk to you about Genesis 1, the first book of the Bible. I know you’ve done a lot of thinking about this. Sometimes you hear people speak of this material as if it’s so ancient and irrelevant to our current lives; and also that if you were interested in science, you’d have to dismiss the other. Neither of those are true, are they?

JOHN WALTON: No, neither of them really hit it on the head. It’s important that we read the Bible for what it is, so we certainly don’t want to read it as if it’s a modern science book. But at the same time, we don’t want to just read it as something that’s ancient and therefore irrelevant. It is ancient, and I think that we need to read it as an ancient text. So often today when people find it irrelevant it’s because they’re trying to read it as a science text and find that it’s inadequate. That’s not a surprise. It’s an ancient text. Those who take the Bible seriously should still think in terms of this was not written to us. People may well feel that it was written for them as they take it seriously. But it still was not written to us – it’s in an ancient language, in an ancient culture, and that’s very important.

SIMON SMART: There are certainly many Christians who take it as if it’s almost a science textbook, but do you think they’re going wrong when they do that?

JOHN WALTON: Well, I think that they are. We need to read the text for what it is. Otherwise we’re not doing justice to the text. If we make it say things that it never intended to say, then we’re imposing our own viewpoints on it and that’s not a good thing. Some people seem to think that if God was the one who wrote this – and of course lots of people make that connection – then He would write it for me. But it really doesn’t work that way – it’s written to someone else.

SIMON SMART: What happens when you do take the ancient context seriously? What do you find in Genesis 1?

JOHN WALTON: Well we find that they are viewing the world the way that everyone at the time viewed the world. People in those days believed in a flat earth, they believed in a solid dome of the sky that held waters back because waters came down sometimes. They believed that the sun, moon and stars and also the birds were all in that same sphere of operation – they didn’t look up at the moon and think ‘oh, that’s a rock floating in space reflecting the light of the sun’. It was entirely different. So, when communication takes place, it needs to be based on what’s familiar; so when the authors of Scripture wrote, they wrote in those terms that would be familiar to their audience. The Bible isn’t trying to tell people what the shape of their cosmic geography ought to be – flat earth, solid sky, things of that sort. For those who think that the Bible has authority, even the Bible’s authority is not vested in those kinds of details.

SIMON SMART: What was the writer of Genesis 1 trying to convey?

JOHN WALTON: In the ancient world when they thought about creation, I’m convinced that they weren’t thinking about material origins. I mean, that’s what we think about when we think about creation, when we talk about God creating. We very easily think about that in material terms – He made stuff. Objects. Material things that we sense with our senses. But in the ancient world, they weren’t so much interested in the material cosmos. Obviously, they were aware of it, but they weren’t interested in it. They were interested in functions, order, organisation, who’s in charge, who makes this thing work. It’s kind of like when you go to work for a new company – you’re not so much interested in who built the building, you’re interested in where you fit into the corporate plan, who you answer to, who’s your boss, who writes your paycheck, who does your evaluations. It’s how it works, how the company’s organised, how it functions. And in the ancient world they were much more interested in functions than they were in material. And so, when they talk about creation, and origins, they’re interested in that kind of question, not in the material stuff. So, I would contend that Genesis 1 is an account of those functional origins – God setting it up to work under His rule.

close -

Genesis 1 and modern science

Professor John Walton on the relationship between Genesis 1 and modern science.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: You’re obviously not someone who thinks taking science and these ancient texts seriously is opposed.

JOHN WALTON: No, I don’t, as you can hear from my understanding of the text; I don’t feel like it’s trying to give us a modern scientific way of thinking. Yet at the same time, it doesn’t bend to science. And what I mean by that is that in the biblical way of thinking, just because something might happen that you can explain in naturalistic ways wouldn’t mean that God hadn’t done it. Rather, the biblical viewpoint would say – no, now you’re just understanding more about how God works and how he acts. So the psalmist says “you knit me together in my mother’s womb”. That doesn’t cancel out all of embryology. It rather says, as much as we can understand about embryology and that whole process from conception to birth – the science is there, we are benefitted by it, we appreciate everything it offers – that doesn’t rule out the fact that that’s how God is knitting us together in our mother’s womb. So it’s not a kind of situation where you have to figure out on every point is that something God’s doing?, or is it something science is doing? and that once you figure out that science is doing it, it means well that’s not God anymore. God is working through those processes. And even when that gets to very complicated processes like evolution, to say – whatever is true about evolution, that would explain what God is doing, give us a mechanism for how God is doing it. There’s a little more room for that once you read Genesis 1 as I suggested, as it’s really more concerned with functions and order and organisation rather than material origins.

SIMON SMART: Does reading the text in the way that you’re suggesting overcome problems with the age of the earth?

JOHN WALTON: Oh yes, because most people who think that the earth is very young get that from the seven days in Genesis 1. If Genesis 1 is not about material origins, and those 7 days therefore don’t have anything to do with the length of time over which material came into being, then Genesis 1 does not tell you the age of the earth. If Genesis 1 does not tell you the age of the earth, then we don’t have a biblical view of the age of the earth, and we’re free to explore whatever science offers to find out whether we think it has legitimacy or not.

close

Articles

-

How should we read the Bible’s account of creation?

Simon Smart on the different ways to read the Genesis creation account.

-

Categories of creationists … and their views on science

Chris Mulherin on the different views of creation among Christians, and how perceived conflict between creation and science can be due to a “confusion of causes”.

-

The genre of Genesis 1: an historical approach

John Dickson on the importance of giving consideration to both the literary style and the historical setting of Genesis 1.

-

The purpose of Genesis 1: an historical approach

John Dickson on what a Babylonian creation myth reveals about the purpose of Genesis 1.

Engage

- Sketch an image that describes what you believe about how the world began. Afterwards, share what you drew and why you drew it with the person next to you.

- Brainstorm the issues or problems that you think might exist when trying to reconcile what you know about the Bible’s account of creation with modern scientific theories about the creation of the universe and the evolution of life.

- Place a mark on this line to answer to what extent you agree with this statement: “Science and the Bible are incompatible”.

Understand & Evaluate

- In small groups, watch the video interview/s with one of the three scholars: John Dickson, John Lennox, or John Walton.

- Complete this Connect-Extend-Challenge table for the interview you watched.

- Discuss and record your answers to the following questions:

-

- What is the main argument of the video?

- What are some reasons given for why the scholar thinks the Biblical account of creation can be read in harmony with modern science?

- What do you think are some of the main strengths and/or weaknesses of their argument?

-

- Present your answers to the rest of the class.

- Complete this Connect-Extend-Challenge table for the interview you watched.

- Read the article from Simon Smart. In your opinion, which of the ways of reading Genesis that Simon outlines makes the most sense to you?

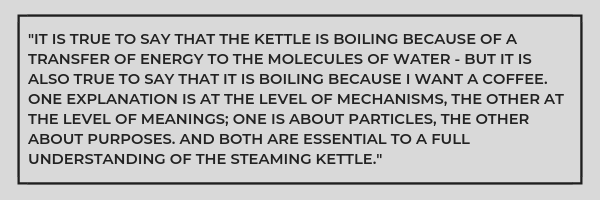

- Read the article from Chris Mulherin. Thinking about the kettle analogy he describes, discuss the following questions:

- How could both Christians and modern scientists be guilty of ‘confusing causes’ when it comes to thinking about the creation of the world and the life in it?

- In your opinion, does the kettle analogy help to reconcile the Bible’s account of creation with common scientific belief? Can you think of any other analogies which could also be helpful?

Bible Focus

Read Genesis 1:1-2:3 and Psalm 33:6-9.

- What do you think is the genre of these passages?

- What are the key things that these accounts of creation are attempting to convey?

- What information about creation do these passages not give us?

- The Bible’s creation account is written to illustrate big truths about the world and our place in it. In light of Psalm 33, what implications would there be for us if this account were true?

Apply

- Imagine you are publicly debating someone who is arguing that belief in science and the Bible’s account of creation are incompatible. What arguments could you use to challenge their views? What extra information would you like to have to build your argument?

- What questions or doubts (if any) do you still personally have about how the Bible’s account of creation might be compatible with modern scientific theory? Write these on a post-it note to be displayed in the classroom.

- Complete the ‘I used to think … Now I think …‘ Thinking Routine in light of the information and opinions you have explored in this lesson.

Extend

- Read the two papers by John Dickson – The genre of Genesis 1: an historical approach, and The purpose of Genesis 1: an historical approach. Write a one-page reflection on the ideas presented in these papers that you found interesting and that shed further light on how to read Genesis 1.

- Explore the bite-sized video interview clips from CPX’s Science vs Faith collection, and write a one sentence summary for three of the videos.