Youth Resource

The genesis of human rights

This segment comes from Episode 2: Rights + Wrongs.

Modern Westerners take it for granted that every life is valuable. But ideas like equality before the law and the importance of caring for the vulnerable are by no means self-evident. So where did they come from? Why are we so attached to the idea of “inalienable human rights”? These segments look at how Christian teachings such as the idea of universal human dignity were foundational in the development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Videos

-

The genesis of human rights

The secret history of a cherished concept.

Transcript

SIMON SMART: On the 10th of December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

ACTOR (UNITED NATIONS DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS):

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude.

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.SIMON SMART: But what’s the basis for such a declaration? Where does the notion of human rights even come from?

The fact is, the very concept of human rights that we’ve come to love and revere has a history. It didn’t just appear out of thin air. Its foundation goes back more than two thousand years.

DAVID BENTLEY HART: I think it’s hard for modern western persons quite to grasp how strange, in long historical perspective, their view of the moral good, of social justice, of what the human person is or the unique almost infinite value of the person in each instance. It simply wasn’t the case in the ancient world. It hasn’t been the case in most of human history.

JOHN DICKSON: So how did we get to the idea of human rights that seems so obvious to us today?

It’s a long and winding road. One that takes us back to this place – the town of Caesarea, in modern-day Israel.

Christianity flourished here. It was a centre of Christian learning and housed one of the largest libraries in the world. But it was also a place of severe Roman persecution of the church.

For a time, it was the home of Basil, one of the great thinkers of early Christianity. What he said about the poor shaped attitudes for centuries.

When Basil arrived in Caesarea in the late fourth century, this place of martyrdom had been restored to a kind of university town – it was the Oxford or Harvard of the Christian world.

But Basil’s studies here weren’t just esoteric or theological. They had a very practical edge for the emerging Christian society. Basil argued that the poor have an inherent claim on the goods of the rich.

ACTOR (BASIL OF CAESAREA): That bread you keep, belongs to the hungry; that coat you have in your wardrobe, to the naked; those shoes which are rotting in your possession, to the shoeless; that gold which you have buried in the ground, to the needy. As often as you have been able to help others, and refused, so often have you done wrong.

JOHN DICKSON: In traditional Greek and Roman thought, only the wealthy and powerful had rights in society. That’s how Nature intended it. But by the end of the fourth century, people like Basil and other Christian intellectuals were arguing that everyone has rights, including, and perhaps especially, the poor. That’s how God intended it.

SAMUEL MOYN: I don’t doubt that Jesus Christ in particular brought about a revolution in thinking of people as equal in the sight of God. Later, this idea of moral equality became an ideal of political equality, and there’s no doubt that that’s caused the world to change drastically.

JUSTINE TOH: The claim that all human beings have rights, regardless of birth, status, or creed, didn’t pop out of nowhere during the 18th-century Enlightenment. Its roots are biblical, and it was Christian thinkers from Basil onwards that shaped the Western concept of “human rights”.

Godfrey of Fontaines was one such thinker. A canon, or church lawyer during the eleventh century, he wrote that everyone has a right and property in common goods in the case of extreme necessity.

In other words, if a poor man stole a loaf of bread from his wealthy neighbour, he wasn’t guilty of theft. He was simply taking what was his by natural right, in order to survive.

It was a slow process, but the seeds of what we now call “inalienable rights” were there in medieval church documents long before the modern period.

NICK SPENCER: This was church teaching that somehow said that all people, irrespective of their capacity or their wealth, demanded some kind of respect. And from that point, you build out the idea that if humans have a dignity, if humans are accountable finally to God, if God is the source of their value, you need to be pretty careful about how you treat them.

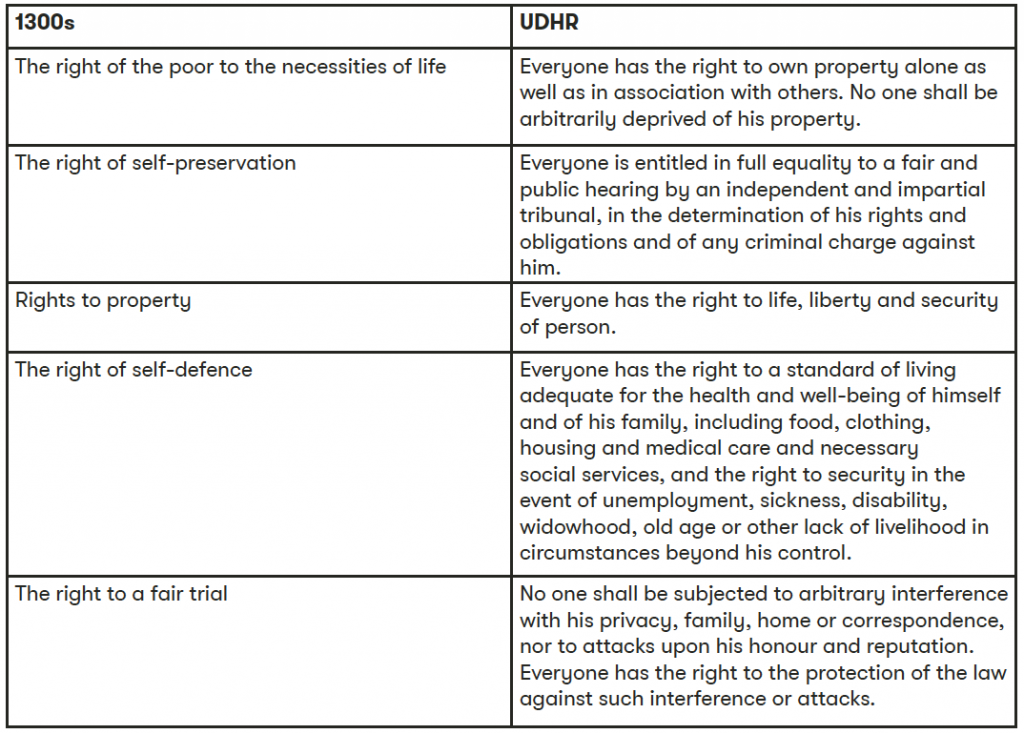

JUSTINE TOH: By about 1300, the following natural rights had been recognised: the right of the poor to the necessities of life, the right of self-preservation, rights to property, the right to a fair trial, and the right of self-defence. All things we take for granted today.

NICHOLAS WOLTERSTORFF: So, here’s a puzzle that I’ve put to my historian friends and none of them has an answer to it. If all of that is true, why the amnesia? Why have people thought it was plausible to say that rights, natural rights, were the invention of the Enlightenment, when it goes back to the Canon lawyers of the 12th century, to the Spanish theologians, to the early reformers and so forth? Why the forgetfulness? And no historian friend of mine has been able to give a good answer to that question.

IAIN BENSON: Any student of human rights or anyone who does any research on it in relation to religion, particularly Christianity, soon realises that the major proponents of human rights as it was developed and codified in the 20th century were themselves Christians, people like Jacques Maritain in France, Charles Malik in Lebanon, these people framed the United Nations Declarations on Human Rights.

NICK SPENCER: In the sense that the Declaration of Human Rights doesn’t draw explicitly on any religious doctrines, of course, it is thoroughly secular. But if you lift the lid you find an awful lot of Christian workings underneath the bonnet.

close

Theme Question

Place a mark on this line for where you think the church falls between restricting and promoting human rights for all.

Engage

- Make a list of five human rights that you think every person should have.

- On 3 May 2011, an international online design competition to create a universal logo for human rights was launched. From the more than 15,300 suggestions from over 190 countries, the winning logo was selected. It was designed by Predrag Stakić from Serbia.

Look at the logo, and discuss what you think it is trying to represent and why you think it won the competition.

- Read the following quotes about human rights. Which one most resonates with you, and why?

- Watch this TED-Ed video for an introduction to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), and write down one thing you learnt.

Understand & Evaluate

Watch the segment: The genesis of human rights

- The segment references five Articles from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Draw or find an image to represent each of these Articles.

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

- Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

- No one shall be held in slavery or servitude.

- Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

- Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression.

- In the late fourth century, in Caesarea, Basil argued that the poor had an inherent claim – a right – to the goods of the rich. How did this contradict traditional Greek and Roman thought?

- How did Godfrey of Fontaines in the eleventh century contribute to the development of the idea of “inalienable rights”?

- Draw arrows to match up each of the natural rights that had been recognised by the 1300s, with a similar article in the UDHR.

- In the segment, Nicholas Wolterstorff comments that many people have forgotten the largely Christian history of human rights. Why do you think this is?

- Read the following quote from Samuel Moyn, and answer the questions below:

- What is your reaction to this statement?

- List three examples mentioned in the video of how Christians contributed to the development of moral and political equality for all.

Bible Focus

Read Proverbs 31:8-9.

- What do these verses say we should do?

- What do they reveal about the inherent existence of rights for the most vulnerable in society?

Read Galatians 3:26-29.

- What do these verses teach about the fundamental equality of human beings?

Apply

- Human Rights Day is held on 10 December every year. Imagine your school is holding a Human Rights Day event. Make a poster for the event, using either or both of the Proverbs and Galatians Bible verses.

- What bases could there be for human rights other than the biblical idea of humans being made in the “image of God” and therefore having inherent dignity and rights?

- Read this quote from Eleanor Roosevelt, the chair of the drafting committee of the UDHR.

- List some ways that you think your community or Australia as a whole could improve in upholding universal human rights.

- Brainstorm ways that you personally could help to promote universal human rights in your community.

Extend

- Choose one of Jacques Maritain or Charles Malik to research. Find information about their life, teaching, and/or written works, and answer:

- How were they involved in the development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights?

- How might their Christian faith have played a role in their work on human rights?